Article | 20 December 2025

Volume 12 Issue 2 pp. 548-560 • doi: 10.15627/jd.2025.32

Integration of light well through generative design to achieve optimal day lighting and natural ventilation: The Case of Deep Plan Buildings in Old Town Pondicherry

Chandrasekaran Chockalingam,* Cibi Balakrishnan

Author affiliations

Vellore institute of technology, school of architecture, Vellore, India

*Corresponding author.

chandrasekaran.c@vit.ac.in (P. Javid)

cibi.cb@vit.ac.in (N. Nikghadam)

History: Received 18 August 2025 | Revised 12 October 2025 | Accepted 22 November 2025 | Published online 20 December 2025

2383-8701/© 2025 The Author(s). Published by solarlits.com. This is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Citation: Chandrasekaran Chockalingam, Cibi Balakrishnan, Integration of light well through generative design to achieve optimal day lighting and natural ventilation: The Case of Deep Plan Buildings in Old Town Pondicherry, Journal of Daylighting, 12:2 (2025) 548-560. doi: 10.15627/jd.2025.32

Figures and tables

Abstract

A case of urban densification in heritage towns like Pondicherry has led to deep-plan wall to wall layouts, where the depth of the plot is considerably more than its width and multi-storey buildings with limited access to day light and natural ventilation. With the recent multi-storeyed developments, passive strategies are essential for achieving thermal and visual comfort. This study investigates the integration of light wells as passive systems to enhance day lighting and natural ventilation to improve indoor environmental quality for a deep plan building in such contexts. In the case of heritage town of Pondicherry, a typical base case sample deep plan residential plot of size 6m width and 20m depth with stilt with three storeys building of 14.4m height, was modelled using Rhino 7, and analysed using Grasshopper, Ladybug tools 1.5.0, Honeybee Radiance, and Design Builder 7.3.100.3 Evolutionary generative simulations were conducted for daylighting analysis to evaluate variations in the size, number, and placement of light wells and Design Builder 7.3.100.3 with Energy Plus 9.4 for CFD analysis for natural ventilation and indoor air temperature. After multiple generative design in accordance with the ECBC 17, filtered 7 options for best UDI results and these options were evaluated for natural ventilation by CFD analysis for the hottest and coolest hour. It was found that double light wells arranged perpendicular provided optimal results, with mean UDI above 50% and ACH ranging from 5.06 to 1.33. All high performing light well has a volume of more than 20% of the total built-up volume. Further the double rectangular light wells with dimension of 3.5 x 2.5 meters yielded the most effective results. This research offers a novel approach to design of light wells using generative design method for integrating passive daylight and ventilation systems in dense heritage urban settings. It demonstrates how generative design can guide regulatory development and sustainable solutions for tropical climates.

Keywords

deep plan building, light-well, evolutionary generative design, daylighting and natural ventilation, heritage area

1. Introduction

The increasing population in the heritage areas of historic cities, coupled with the high value of urban land, has necessitated the development of high-rise, deep-plan, and compact buildings. A deep-plan building is characterized by a floor depth that significantly surpasses its width, thereby complicating the achievement of a high skin-to-volume ratio that facilitates the penetration of daylight and natural ventilation into most interior spaces [1]. To address this challenge, architects frequently incorporate light wells—vertical voids or atria within buildings that serve as passive systems for natural lighting and ventilation [2-5]. This study focuses on deep-plan multi-storey residential buildings situated within heritage zones, with the objective of evaluating the performance of light wells in achieving indoor comfort and deriving the volumetric ratio of the light well to the total building volume under hot and humid climatic in dense urban context. The key design parameters, such as size, location, orientation, window dimensions, and number of light wells required, remain inadequately defined for this context. Consequently, this study investigates the parameters essential for designing efficient light wells in deep-plan buildings, with the aim of informing a potential regulatory framework in volumetric ratio for heritage areas in Pondicherry. This study was confined to a single representative building used as a base case for simulation and analysis, rather than encompassing the entire neighbourhood context. The findings provide indicative design parameters that offer preliminary insights, necessitating further validation across multiple building types and urban settings.

Previous studies have often examined the daylighting and ventilation performances of light wells separately. However, modifications to the configuration of a light well influence both aspects simultaneously. In this study, the light well was approached as an integrated system for daylight and natural ventilation within the dense heritage fabric of Pondicherry. In recent years, many residences have become increasingly reliant on mechanical air conditioning and artificial lighting. This study explores how passive strategies can serve as sustainable alternatives. Based on the light-well design outcomes, guidelines for heritage areas were developed, focusing on the volumetric ratio of the light well to the total building volume. Overall, this study examined the light well as an architectural system that integrates daylighting and natural ventilation in deep-plan buildings within dense heritage areas, offering insights that may also be applicable to other climatic contexts.

2. Literature review of daylighting and nature ventilation performance of light-wells

Light wells are architectural features increasingly employed in urban and tropical contexts to improve indoor environmental quality by enhancing both daylighting and natural ventilation, which is critical in optimizing passive building design strategies, particularly in dense urban environments and deep-plan buildings. The utilization of light wells is prevalent in many tropical regions. Studies have demonstrated that employing light wells for illumination and natural ventilation can result in substantial energy savings, reaching up to 25% of total energy consumption [6].

Several studies have examined the effectives of light well in improving indoor daylight availability. The geometry of light well including height, width, depth, and cross-sectional shape has been identified as a key determinant of their daylighting performance. For instance, Kristl and Krainer [1] analysed how geometric configurations influence illuminance levels using scale models and the daylight factor as a primary metric. Similarly, Amin et al. [7] introduced design modifications in light well profiles employing a wider upper and narrower lower section to improve daylight penetration in hot and dry climates, achieving better light distribution. Other influential variables identified in the literature include orientation, plan form, height and width of the light well [8-12]. In recent years, simulation-based studies have increasingly used dynamic daylight metrics such as Daylight Autonomy (DA) and Useful Daylight Illuminance (UDI) to provide more accurate performance assessments under real climate conditions. For instance, Ahadi et al. [13] investigated square-shaped light wells of varying sizes and orientations using DA as a performance criterion, highlighting the advantages of non-rectilinear configurations in deep-plan layouts.

Natural ventilation is another critical function of light wells, especially in tropical climates where passive cooling can substantially reduce energy consumption. Studies have identified key design variables affecting airflow performance, including void placement, light well height, cross-sectional form, and connection to outdoor spaces. Kotani et al. [14-16] conducted experimental studies on light wells connected to horizontal voids, measuring airflow patterns, rates, and temperature gradients. Their findings indicate that light wells can facilitate cross ventilation, particularly when configured with appropriate inlet and outlet openings. Other studies, such as those by Muhsin et al. [17], combined field measurements with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations to assess the role of light wells in multi-storey housing units in Malaysia. Their results revealed that indoor air velocity was generally insufficient for thermal comfort, but could be significantly improved by enlarging the light well footprint to encompass 50% of the living unit area, resulting in a 50.88% increase in ventilation performance. CFD-based investigations have also explored the impact of void positioning (horizontal vs. vertical), indicating that airflow is highly sensitive to both geometric configuration and external pressure differentials [18]. Furthermore, some research has shown that light wells designed solely for daylighting are effective only up to two floors [15], limiting their utility in high-rise applications unless specifically optimized for airflow.

Although extensive literature exists on daylighting and ventilation performance separately, few studies have addressed their synergistic or competing effects. Integrating these two aspects is crucial because design modifications that enhance one may compromise the other. For instance, increasing the width of a light well may improve daylighting but reduce cross-airflow, whereas increasing its height may boost ventilation but reduce daylight penetration at lower levels. The lack of integrated design strategies in the literature indicates a significant knowledge gap. There is minimal research on generative or optimization-based approaches that simultaneously evaluate daylighting and ventilation performance, especially in complex urban conditions where design flexibility is constrained. With the advancement of simulation tools, environmental plugins like Ladybug, Honeybee combined with Rhino 3D, Grasshopper, and DesignBuilder with Energy plus, it is now possible to model and optimize light well performance under real-world environmental conditions. These tools enable the generation of multiple design iterations and performance evaluations using parametric and generative design methods.

The integration of climate-responsive design parameters including light well volume, geometry, WWR (Window-to-Wall Ratio), and void positioning offers a pathway to create optimized design solutions for deep-plan buildings in heritage-dense tropical urban environments. This constitutes a novel research area with considerable potential to advance energy-efficient design solutions in the future. This study addresses this gap by employing a generative design methodology to investigate optimal light-well configurations for daylighting and specific hours for ventilation performance. The findings aim to contribute a replicable framework for future sustainable architectural design and urban infill strategies.

3. Methodology

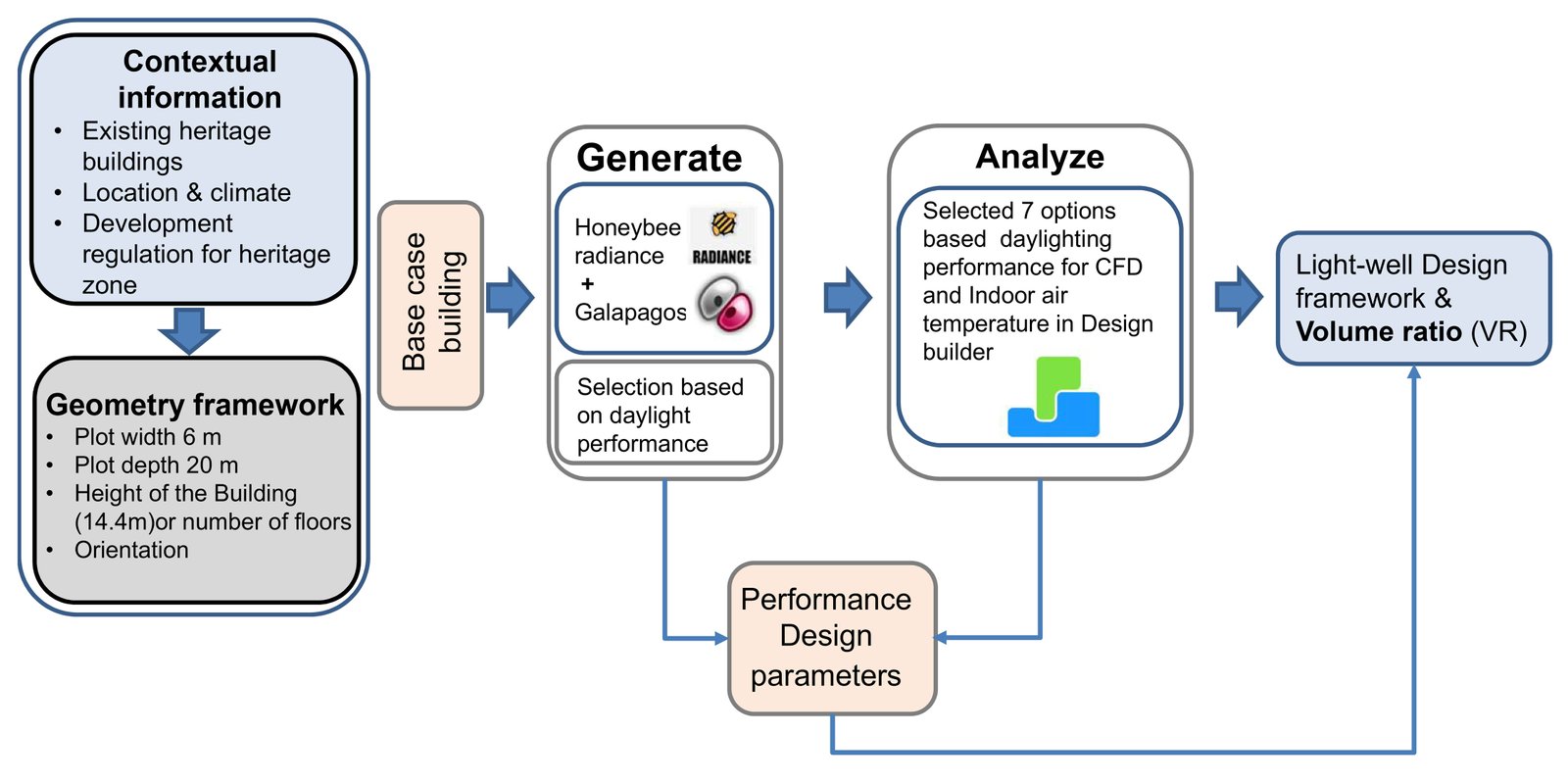

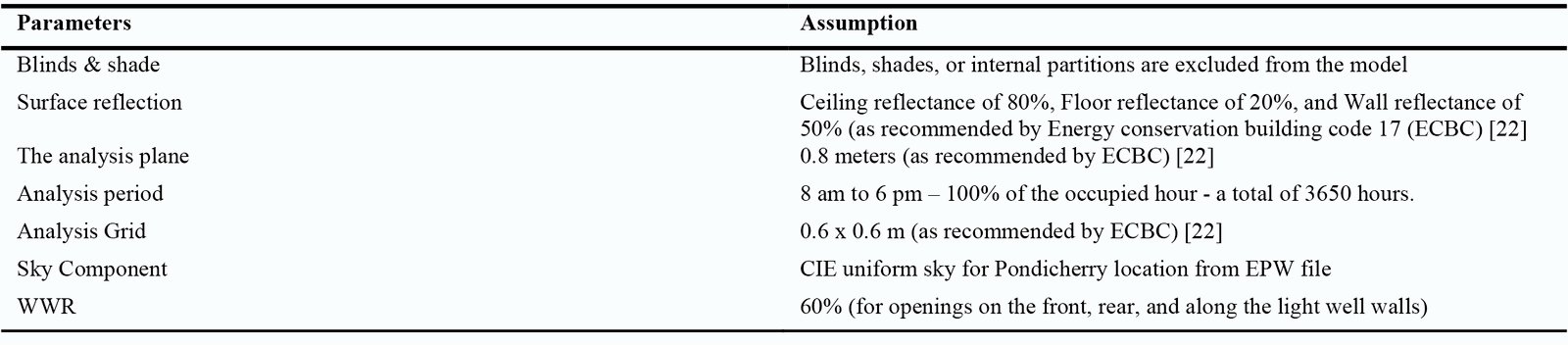

In the literature review, it was identified that the independent variables influencing the daylighting and natural ventilation performance of light wells include the area, height, orientation, plan form (square or rectangular), size, position, number of wells, and openings. Additionally, the ratio of the volume of the light well to the total building volume is a significant parameter in defining the design of the light well. A base case model was developed in accordance with the planning authorities for this type of residential development in a small deep-plan plot with a size of 6 meter wide and 20 meter depth as a base case sample. The Useful Daylight Illuminance (UDI), a dynamic daylight performance metric, is particularly accurate for tropical climates with substantial cloud cover [18]. UDI is employed in this research as a climate-based metric, defined as the percentage of occupied time when a target range of illuminances at a point in a space is achieved by daylight. According to ECBC 17 [19,20] for residential buildings, the illuminance range is 100–2000 lx, with a mandatory provision of 45% of the floor area for 90% of the occupied time. Honeybee Radiance was used as a plug-in package in Grasshopper to determine the UDI based on the EPW weather file data for Pondicherry, and the assumptions are listed in Table 1. In terms of natural ventilation, airflow is driven by wind and buoyancy through the openings in the building envelope. The light well acts as a cross-ventilation shaft using passive ventilation. In this study, the air velocity, ventilation rate, and airflow pattern within the entire floor were considered as criteria for natural ventilation efficiency. From the selected options demonstrating optimal UDI performance, Design Builder version 7.3.100.3 was employed for CFD simulations and to predict the airflow pattern within each floor. Honeybee Radiance and Design Builder were used for daylight and ventilation simulations, respectively. These tools were selected because of their established efficacy in modelling intricate building geometries and environmental conditions. A concise validation, grounded in previous studies that compared simulated and empirical results [21,22], was presented to affirm the reliability of both tools for application in tropical residential settings. Figure 1, illustrates the research methodology flowchart and the tools employed in this study.

The research stages were as follows:

- Examination of the climate of Pondicherry and documentation of the current conditions of deep-plan buildings.

- Development of a base case building in accordance with the Pondicherry planning authority for a deep-plan plot to establish the project framework.

- Daylight analysis was conducted using Ladybug and Honeybee Radiance, along with Galapagos for the generative design of light wells. Galapagos was employed to iterate and optimise the geometric parameters of the light wells, such as the height, width, depth, and number of wells, to achieve the green building benchmark for Useful Daylight Illuminance (UDI).

- Utilising the filtered results from the daylight performance analysis, seven options were selected based on UDI results, and Design Builder was employed for CFD analysis to assess the natural ventilation rate during the hottest and coolest daytime hours of the year.

- Based on the derived results, the volumetric ratio of the light well to the deep plan was determined to optimise the performance in daylight and natural ventilation.

- Proposal of a model framework for the light well volumetric ratio of the total built-up area in the heritage zone.

3.1. Climate of Pondicherry and existing situation of deep plan buildings

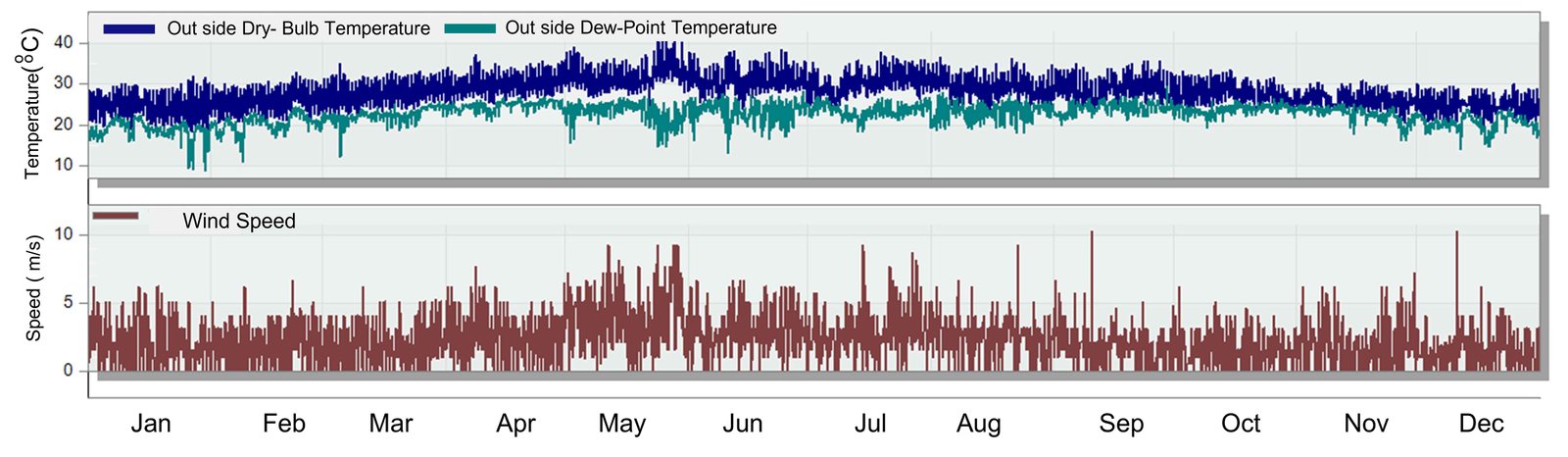

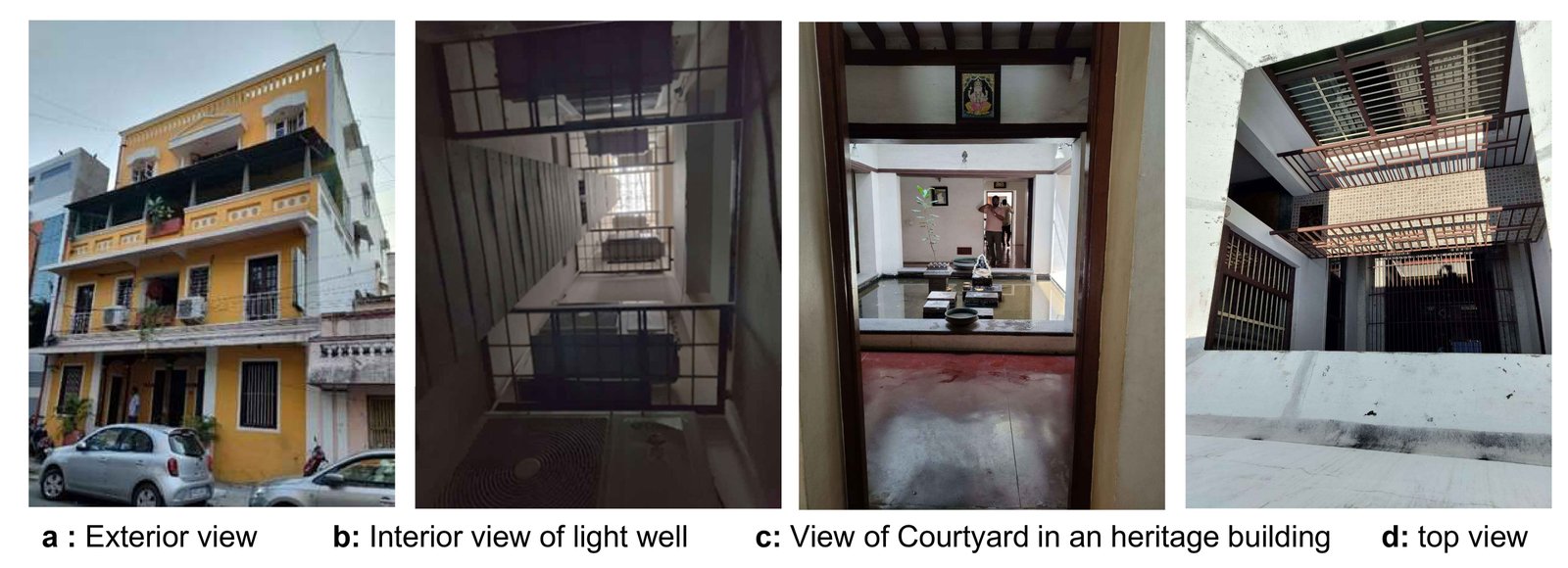

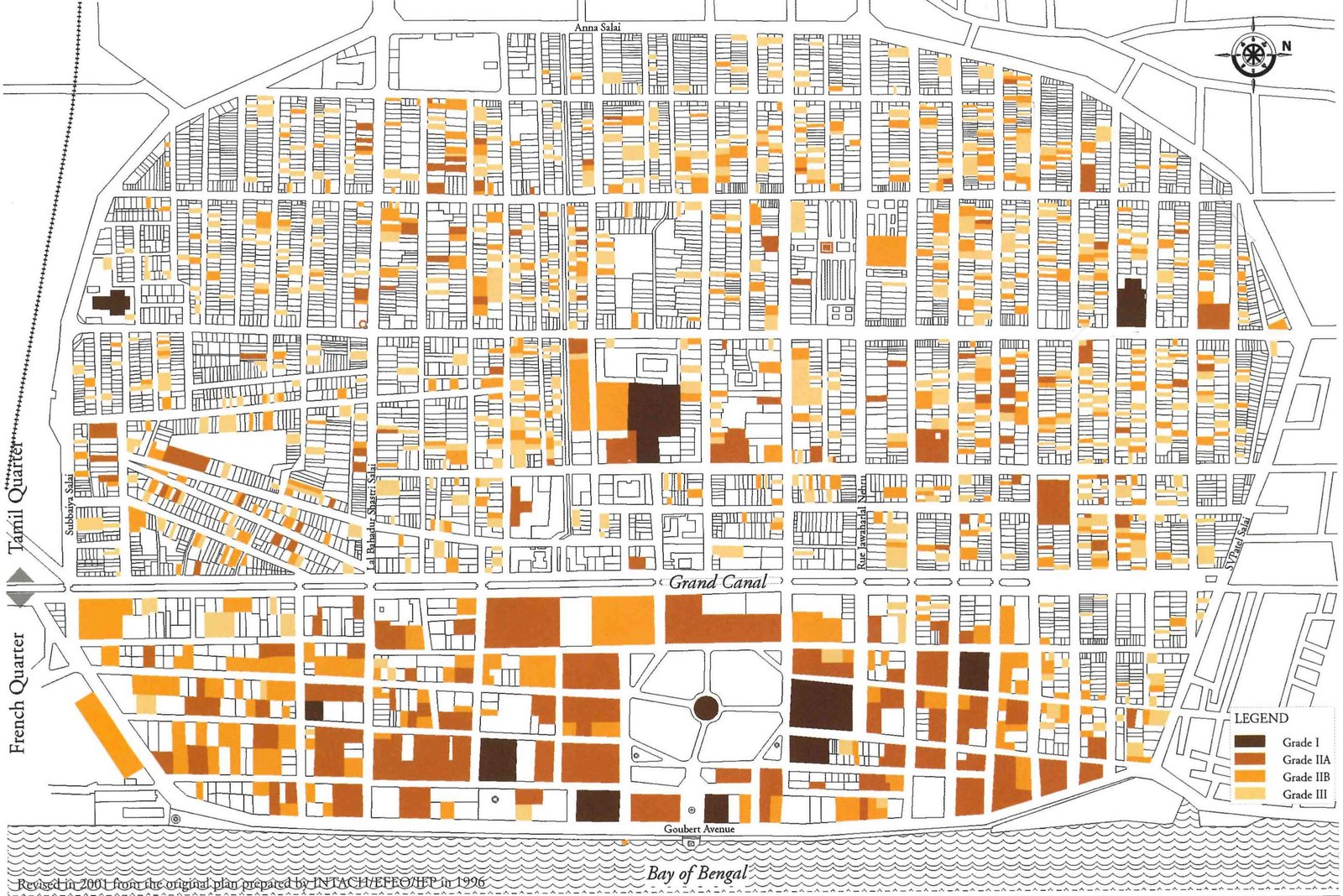

Pondicherry is situated at a latitude of 11.55°N and a longitude of 79.49°E. According to the Köppen climate classification, Pondicherry experiences a tropical Savanna climate, that of coastal Tamil Nadu. Specifically, it is categorized as the dry-winter type (Aw), bordering the dry-summer type (As) [23]. Throughout the year, temperatures typically range from 36°C to 28°C. The region receives an average of 3407 hours of sunlight annually, out of a possible 4383 hours, equating to an average of 10.96 hours of sunlight per day. The predominant wind direction in Pondicherry is from the south, southeast, and southwest, with wind speeds ranging from a minimum of 1 m/s to a maximum of 5.6 m/s as hourly average wind speed, as depicted in Fig. 2. The hottest daytime hour is May 18th 3 pm and coolest daytime is January 5th 9 am from Fig. 2. Pondicherry is often referred to as "India’s Little France" or the "Window of France," owing to the aesthetic appeal of the buildings along the Boulevard. The "Boulevard town" was constructed in an oval shape and divided into a European section known as "Ville Blanche" or the "white town," and a Tamil section referred to as "Ville Noire." The research context focuses on the Tamil side, characterized by narrow plots and vernacular colonial-style housing with front and back courtyards as in Fig. 3. The Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) has documented the boulevard area and marked as grades of heritage value as in Fig. 4, has identified about 1195 heritage buildings [24]. A typical residential house of Pondicherry has double courtyards which were predominately single or double storied. Over time, due to family partitions among

Figure 2

Fig. 2. Hourly weather data of Pondicherry: dry bulb temperature, dew point temperature in ºC and wind speed in m/s.

Figure 3

Fig. 3. (a)-(d) Existing deep plan building of Boulevard town heritage area in Pondicherry.

Figure 4

Fig. 4. Documented plan of Boulevard town heritage area with grades of heritage building [24].

landowners, plots have been subdivided into narrow, deep plans, with courtyards transformed into light wells. Due to increased land value and mixed-use development, new buildings have been constructed with 3-5 floors, incorporating open-to-sky (OTS) light wells and ventilation shafts for natural lighting and ventilation.

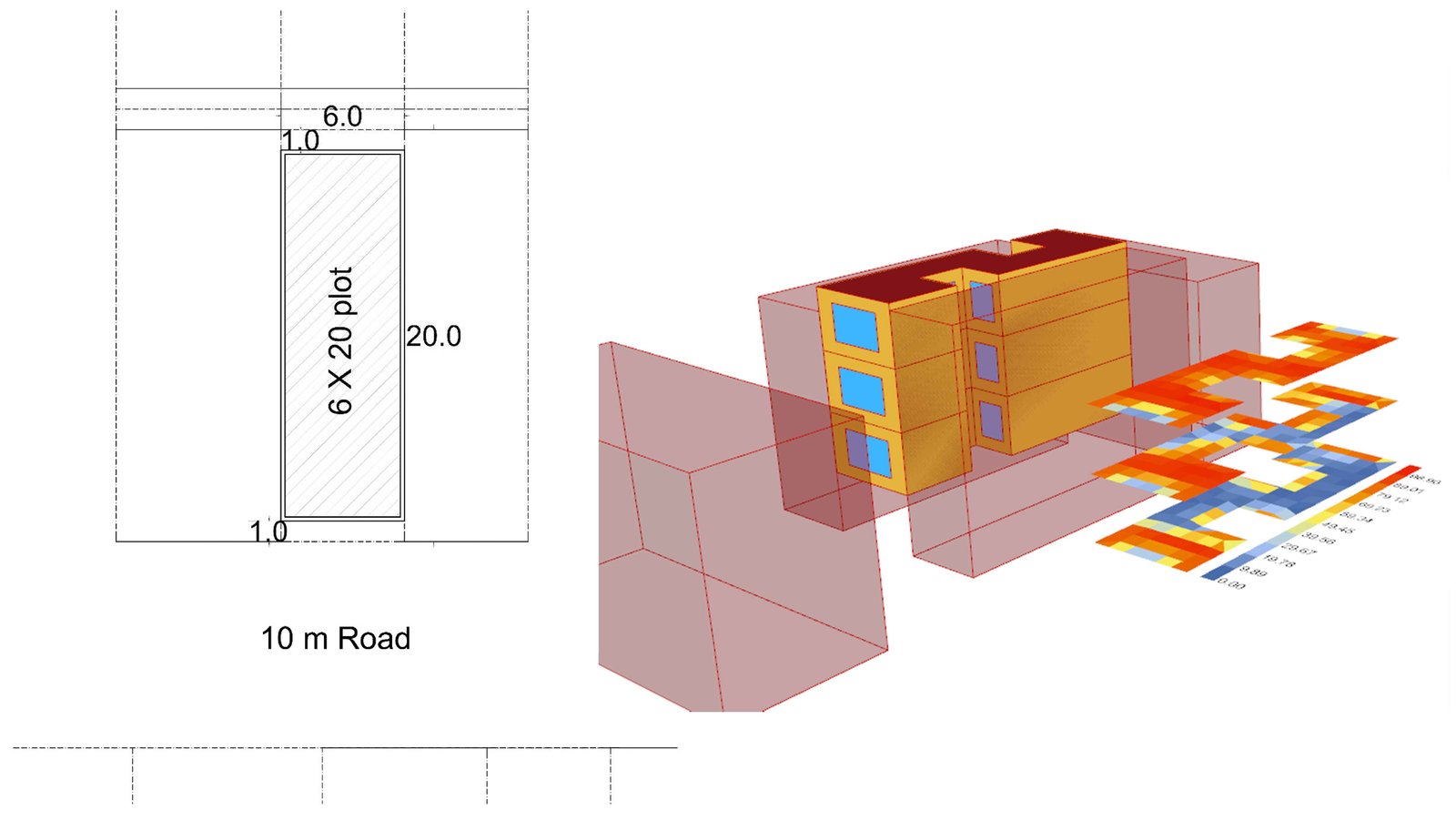

3.2. Base case

In the heritage area of Pondicherry, the existing conditions reveal that the typical deep plan width-to-depth ratio exceeds 1:3, with a minimum plot width of 6 meters. The base case model is situated on a small plot measuring 6 m × 20 m (a ratio of 3.3), featuring stilt on the ground floor for parking and three additional floors above. The front road width is 10 meters, and the total building height is 14.4 meters, with a floor-to-floor height of 3.6 meters. The minimum size of the light well is 3 m × 3 m. Two light wells are present, with an area per floor of 84 m², which is within the permissible plot coverage area of 80%. The Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) for openings on the front, rear, and along the light well walls is 60%. The building development control permissible planning data as in Table 1 and 3D view of the base model with the UDI heat map as in Fig. 5.

3.3. Daylight analysis

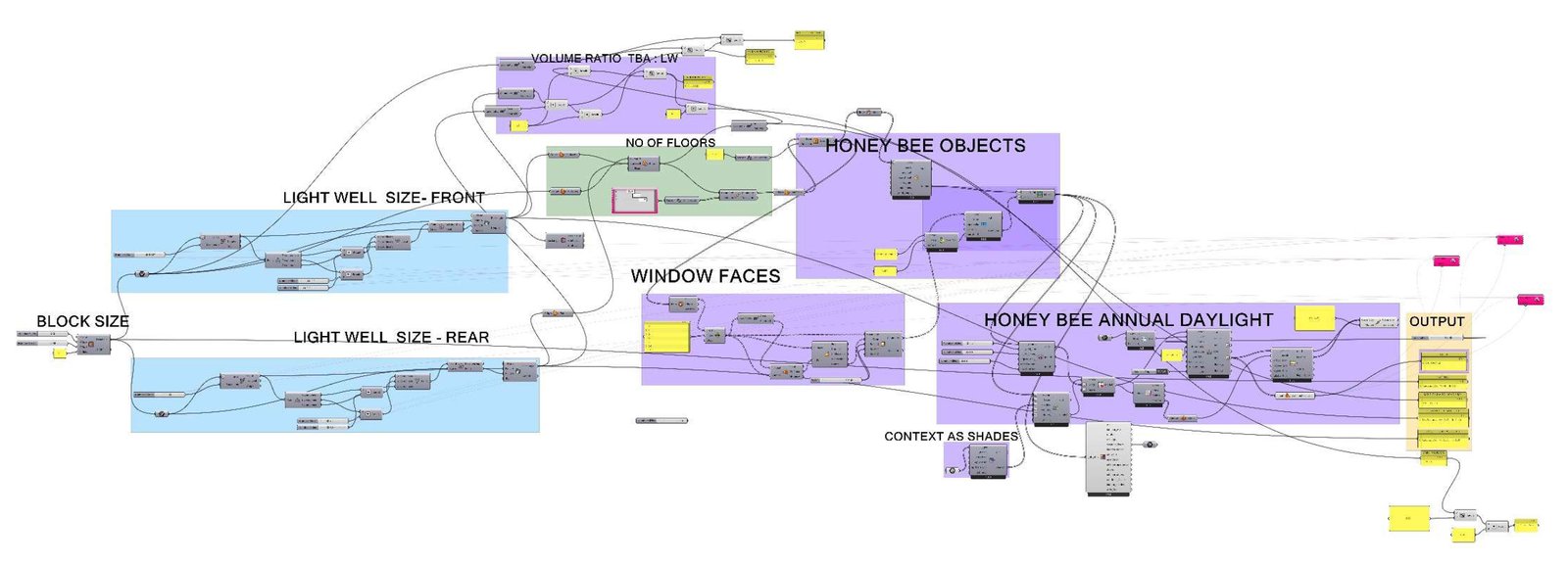

The initial step in this study involves determining the form, the form derived from the basecase sample. All four cordinal orientation, and area ie.. the length and width of the light well to achieve an adequate Useful Daylight Illuminance (UDI) for three residential floors of 10.8 meters in height. The defined model serves as the base case model, with alternatives to the light well that remain within contextual limits. The assumptions used for daylighting simulation are listed in Table 2. The Galapagos evolutionary generative plug-in in Grasshopper is employed to filter the maximum mean UDI combined for all floors as the fitness, the grasshopper script as in Fig. 6. The list of generative parameters as follows:

- Location of the light well on the depth of the plot;

- Length and depth of the light well (area), range: minimum of 1.5m to maximum of 8 m;

- Orientation – North, south, east and west of the main road;

- Single and double light well options.

- total built-up area

Figure 6

Fig. 6. The Grasshopper node for the Daylight simulation for single light well in Honeybee and Galapagos.

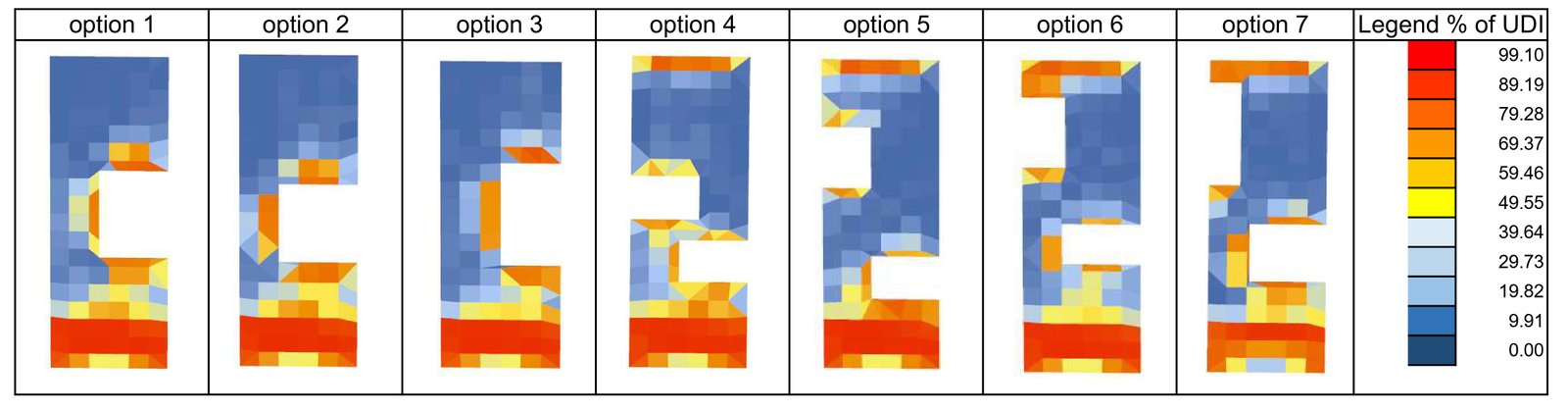

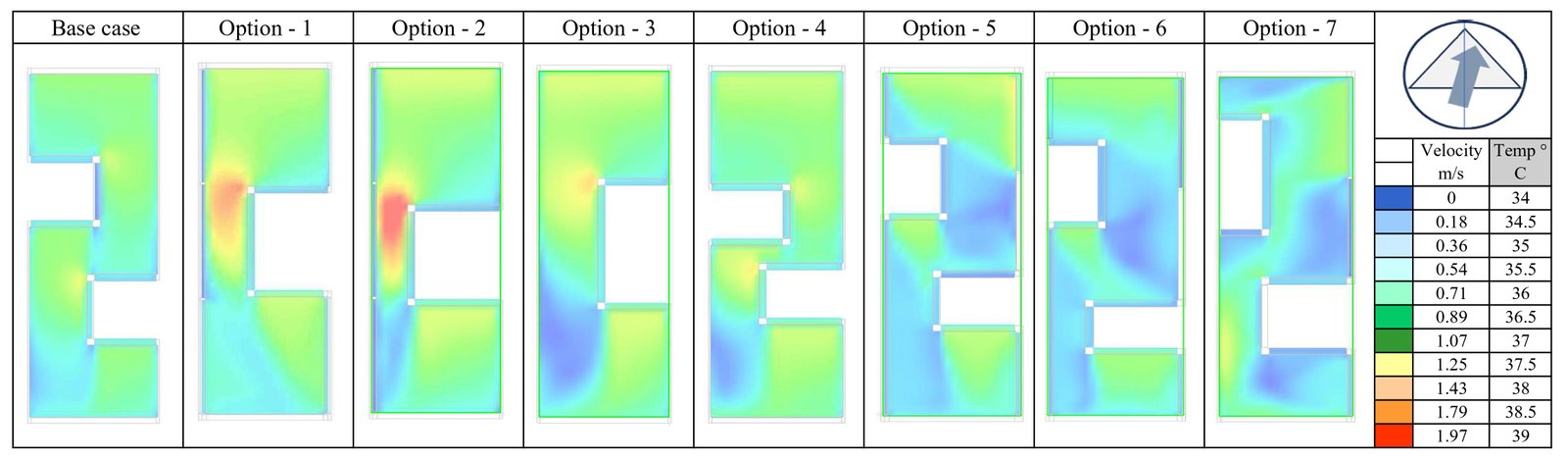

Initially, a Galapagos generative for the location of a fixed size of light well (options 1,2,4,5 and 6) was conducted, followed by generative solutions for random size (options 3 and 7), location, and building orientation, as shown in Table 3. After multiple Galapagos runs, the results were filtered for floor areas less than 90 m² and mean UDI exceeding 45%, in accordance with the ECBC 17 criteria [21] of the floor area. The image of the heat map of the ground floor for all the selected options in Fig. 7 and the grasshopper script in Fig. 6. The Options selected for UDI were more than 45%, as shown in Table 3, option no 1-3 were with a single light well, and no 4-7 were with double light wells.

Table 3

Table 3. Selected options of the Generative results with floor area <90 m2, UDI more than 45%.

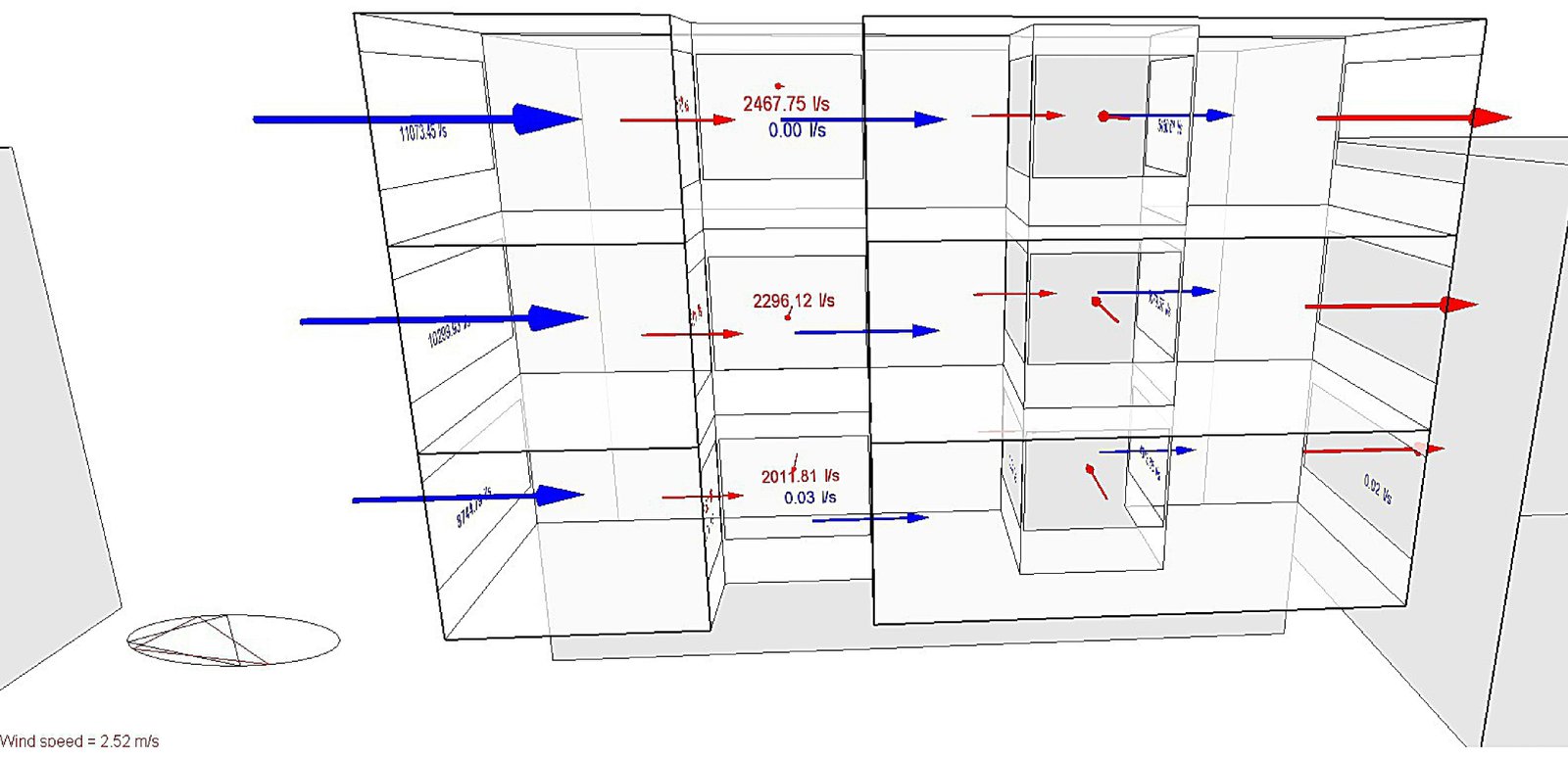

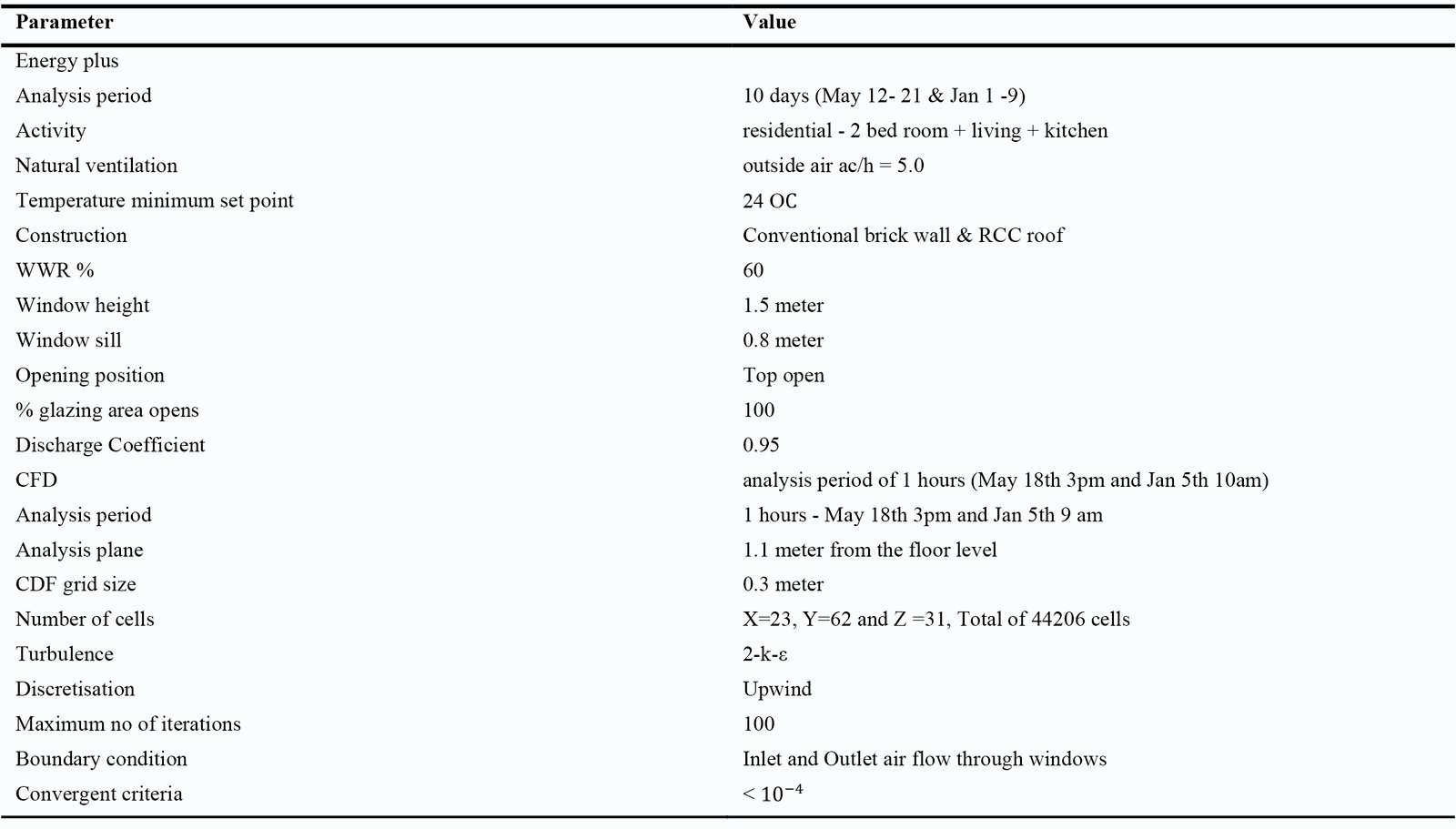

3.4. The evaluation of natural cross ventilation in light-wells with acceptable daylighting performance

It is essential to determine the specific times when natural ventilation can potentially contribute to indoor comfort. The ventilation rate is the volume of air exchanged within a space over a specific time period, usually measured in liters per second. In this study, Design Builder 7.3.100.3 has been utilized as graphical user interfaces for Energy-Plus 9.4 and CFD simulations to predict the airflow pattern inside the deep plan for three floors without interior partitions. We tabulate floor wise and take mean of inlet and out volume in L/s (liters/ sec) as the ventilation rate, using the 2-k-ε (standard) as the turbulence model which is suitable for most indoor airflow simulations. The boundary conditions considered in this study included the inlet and outlet air volumetric flow through all the ventilation openings obtained from CFD simulation data. The convergent criteria set as residuals for turbulence and continuity, the indoor temperature and air speeds were monitored to ensure that they remain stable for 100 iterations. A simulation was run using 50,000 cells, and comparison with coarser and finer meshes showed that the results did not significantly change, proving that the solution is independent of the mesh size and numerically reliable. With the defined bondary conditions, convergent criteria and medium cells the ventilation rate is calculated for the Air Change per Hour (ACH) and indoor air temperature on each floor. The assigned value for Energy plus and CFD analysis as in Table 4.

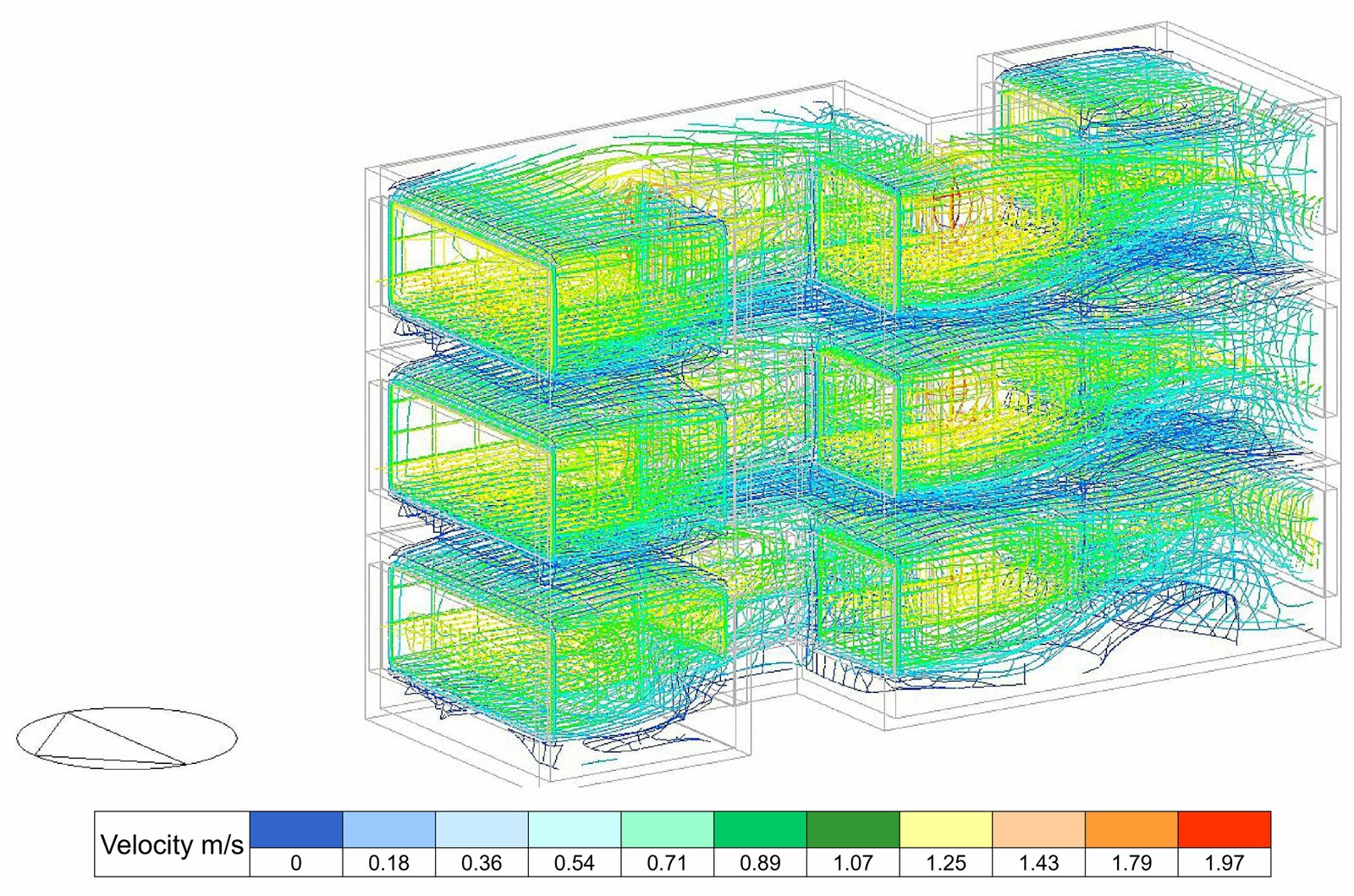

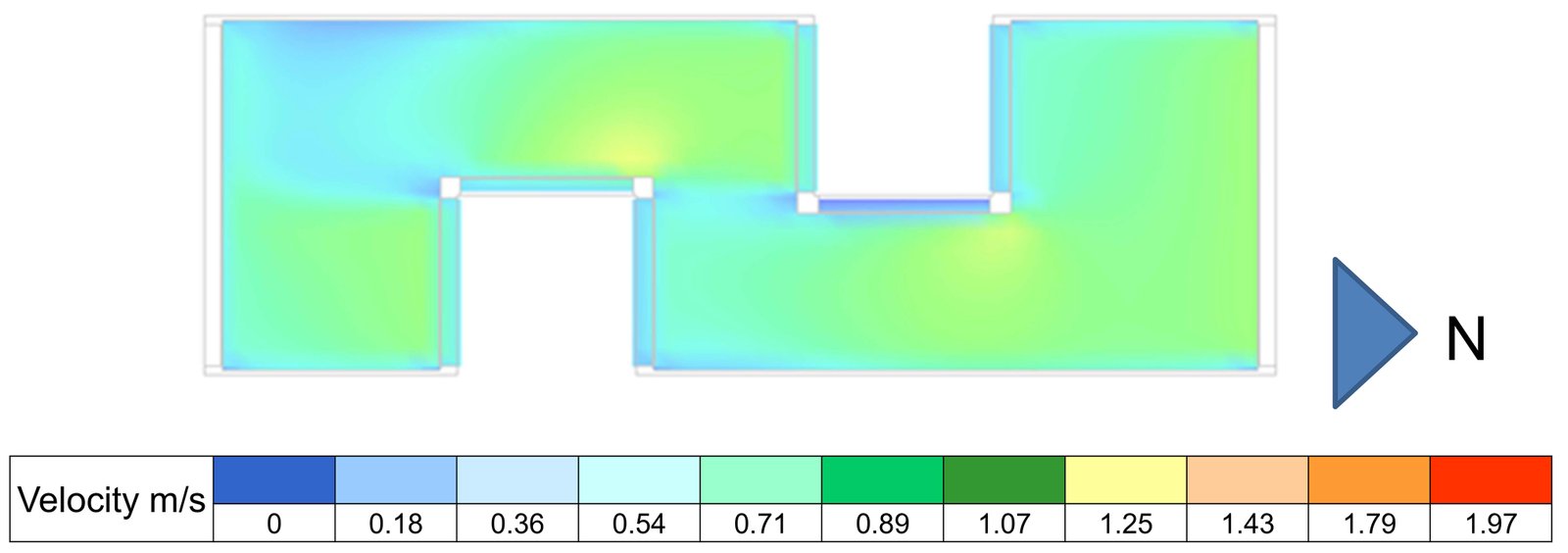

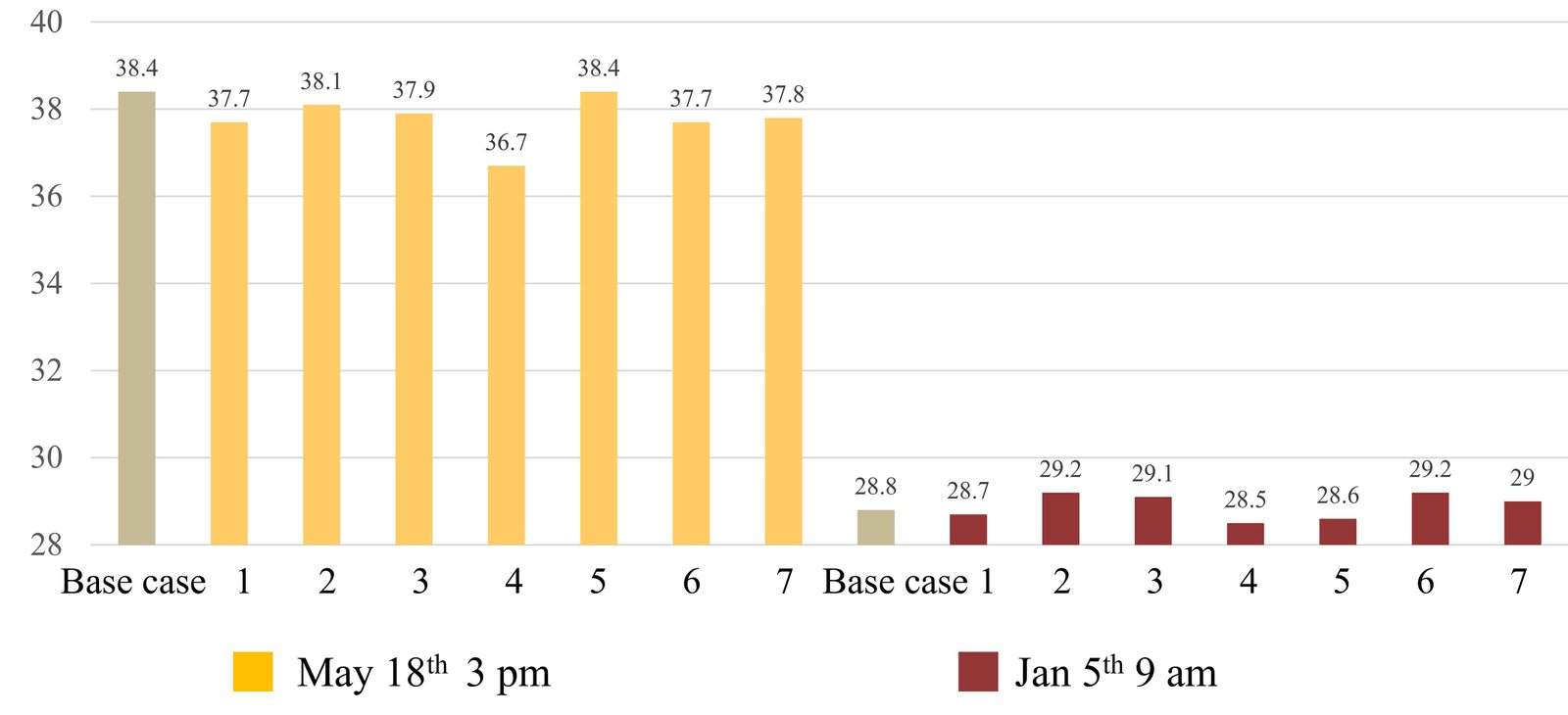

Accordingly, after modeling the selected 7 options of light wells in the Design Builder version 7.3.100.3 simulation program. The hourly weather data are depicted in Fig. 2. May 18th at 3 p.m correspond to the hottest daytime hour of the year and January 5th at 9 a.m. the coolest daytime hour of the year (based on the EPW file and hourly weather data). May 18th is identified as the hottest day, characterized by nearly 100% relative humidity and a higher wind speed of 2.52 m/s, at south west direction and outdoor air temperature of 37.4ºC. January 5th at 9 a.m. represents the coolest with a wind speed of 1.23 m/s, at south east direction and outdoor air temperature of 26.5ºC. From this daylighting analysis results as south facing, the base case model is fixed with south facing the 10 m road as in Fig. 8. The 3D velocity vectors pattern in Fig. 9, and in Fig. 10, the top floor plan view of velocity filled contour pattern.

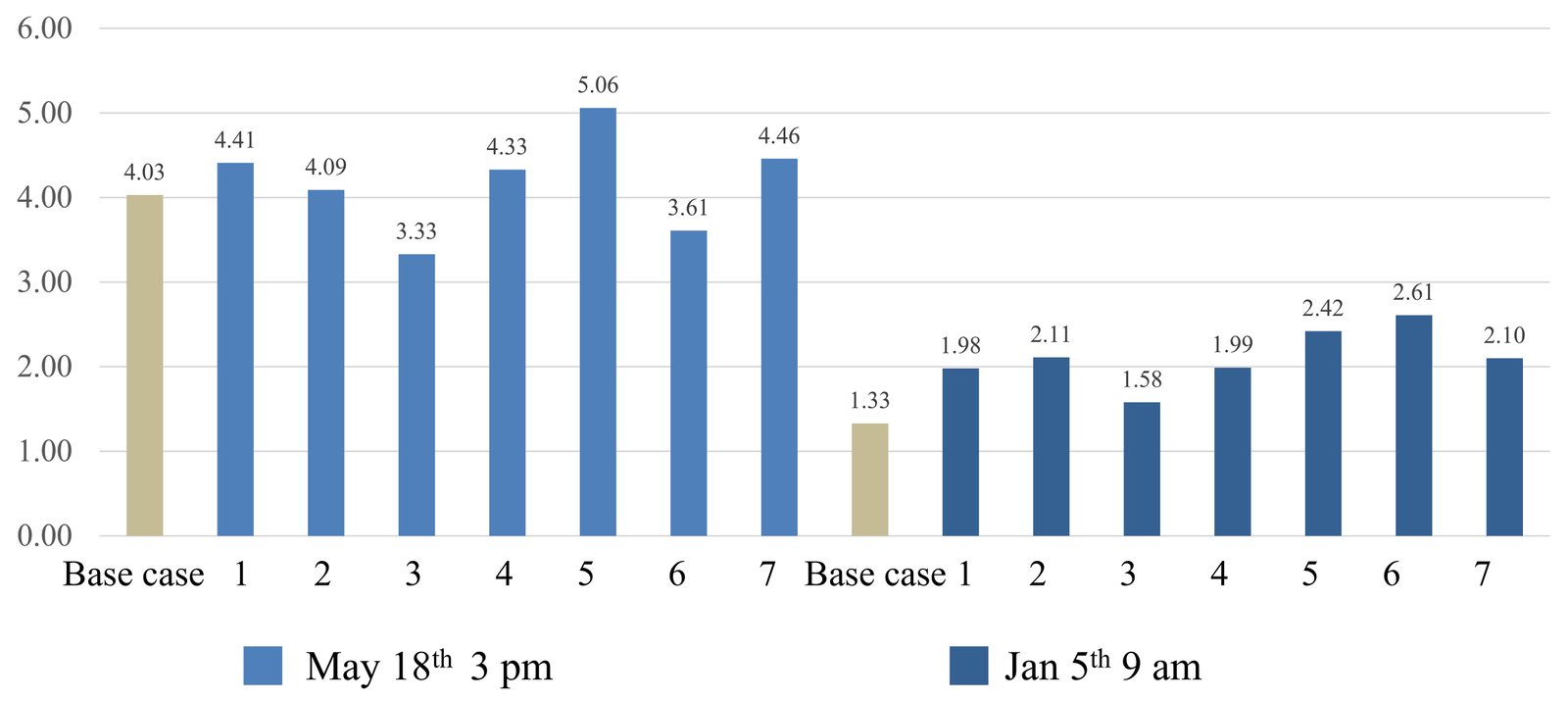

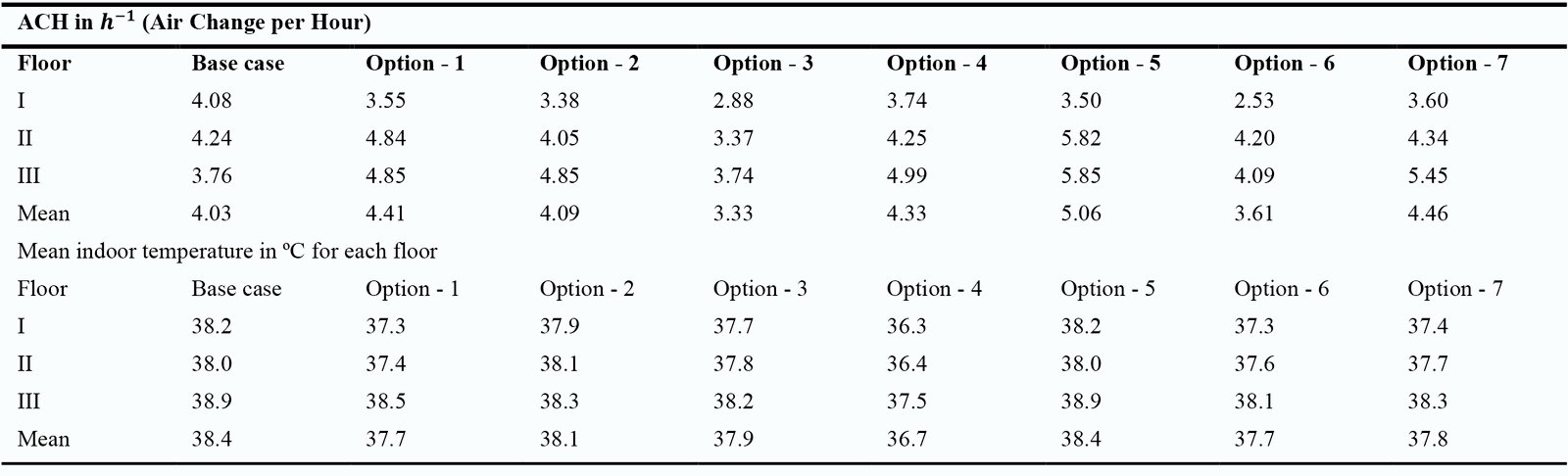

The Air Change per Hour (ACH) is a measure of how many times the air within a defined space (like a room or building) is replaced with fresh air in one hour. Which can be calculated using the ventilation rate for that analysis period with volume of each floor. According to National building code (NBC) part 8, the required air change per hour (ACH) for living rooms 3-6,

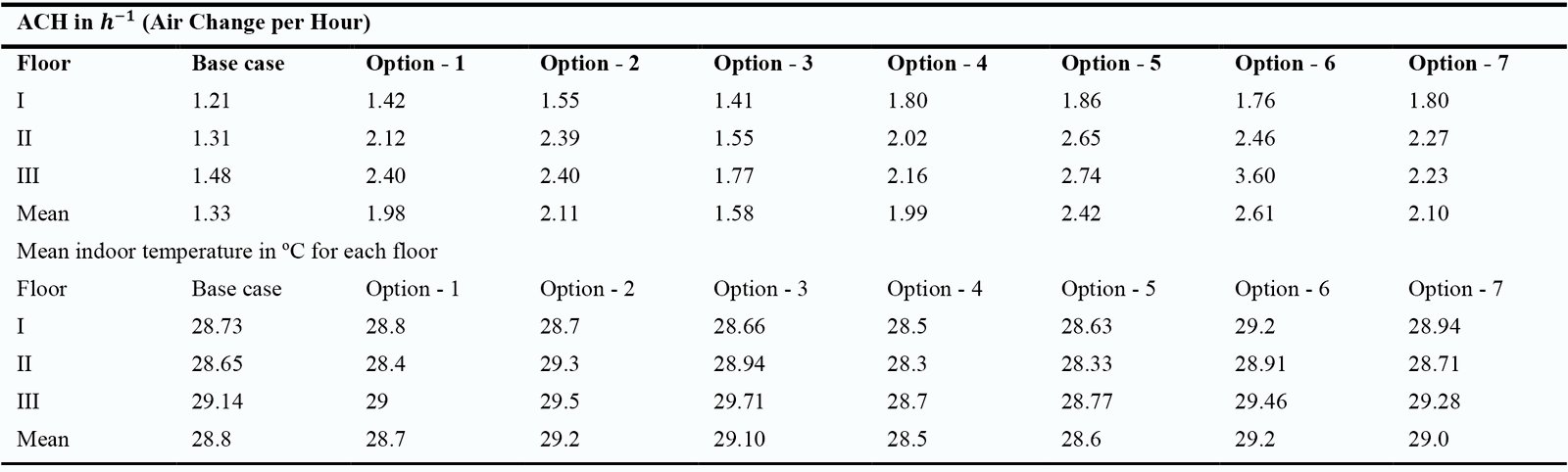

bedrooms 2-4 for a residential use building [22]. The mean indoor temperature for each floor was recorded from the Energy-plus results. The seven options selected from the daylighting analysis were compared with mean ACH and mean indoor temperature for all the habitable floors of the options without internal partitions and rooms. The results are listed for both the analysis daytime hour in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 5

Table 5. The Mean ACH, Mean indoor temperature, and velocity-filled contour pattern for the base case and seven options on May 18th at 3pm.

Table 6

Table 6. The Mean ACH, mean indoor temperature and Velocity filled contour pattern for the seven options on January 5th 9 am, outside temperature of 26.5 and wind speed of 1.23 m/s.

4. Results

After conducting several optimisations runs using Galapagos, the daylighting performance was assessed in accordance with the ECBC 2017 guidelines. The results were refined to include only those configurations with a floor area under 90 m² and a mean Useful Daylight Illuminance (UDI) covering more than 45% of the floor area. The building's orientation facing south, towards the adjacent road, consistently achieved the highest UDI values across all configurations as in Table 3. Among the evaluated options, configurations with double light wells arranged perpendicularly surpassed both single light-well options and the base case model, showing a significant improvement in daylight distribution throughout the floor plate. Additionally, generative design models with randomly sized light wells demonstrated superior daylighting performance in both single- and double-well scenarios, highlighting the potential of non-uniform geometries to enhance daylight access. The natural ventilation performance was evaluated based on the air changes per hour (ACH) and mean indoor temperature across various building configurations and floor levels. The results of CFD analysis indicate that, despite an adequate ventilation rate in the assessed light-wells, air velocity was significantly below the minimum desirable threshold for cooling ventilation (0.5 m/s) for Jan 5th 9am. Conversely May 18th with increased outdoor wind speed the ventilation inside the floor improved, achieving wind velocity of 1-1.97 m/s.

4.1. Observation of daylight analysis

The findings from the daylight analysis elucidate several critical insights for optimizing light-well design in deep-plan buildings. Firstly, the southern orientation consistently yielded the highest daylight performance, with an increase of approximately 2.5–3.7% in UDI compared to other orientations. Secondly, configurations with double light wells surpassed single-well designs, underscoring the benefits of multiple light sources in enhancing daylight distribution. Notably, generative models with randomly sized light wells demonstrated superior performance across both single and double-well configurations, suggesting the potential of non-uniform, performance-driven geometries over fixed-size or conventional forms. Within the double light well category, perpendicular arrangements produced the best results, likely due to improved spatial coverage and daylight penetration angles. Importantly, across all high-performing options, the light well volume ratios ranged between 19% and 26% of the total built-up volume.

4.2. Observation of CFD analysis

A. For the hottest day, with 2.52 m/s wind speed as in Table 5 and Fig. 11.

- The ventilation rate was better in all options with a mean ACH of 3.33 – 5.06 and an indoor temperature of 36.5–38.5°C.

- Higher floors have better ventilation than lower floors, and the top floor has the highest mean indoor temperature.

- Among single court, the option no 1 with well size 3.5 x 5 m located at the centre of the deep plan performs the best for ACH and in the narrow passage on option 2 and 3 have higher wind velocity due to venture effect air flow.

- Among the double court options, the 5 & 7, perpendicular, space apart, and minimum of 3 m wide performed well for ACH with 5.06 and 4.46 respectively.

- Options 4 with light well closer together have lower mean indoor temperature due to its air flow pattern through the light wells at close proximity.

- In options 2 and 3, with more depth and a single light well, the mean ACH is lower than all the options.

Figure 11

Fig. 11. Wind velocity filled contours pattern in top floor plan view Wind direction from South west @ 2.52m/s.

B. For coolest daytime, with 1.23 m/s wind speed as in Table 6 and Fig. 12.

- The ventilation rate is lower in all the options with a mean ACH of 1.33 – 2.61 as the outside wind velocity of 1.23m/s and with an indoor temperature of 28.5–29.2 °C, as shown in 13 and 14.

- Among single court the option no 2 with well size 4 x 4.5 m located at the centre of the deep plan performs the best for ACH

- Among the double court options, 5 and 6, perpendicular, space apart, and a minimum of 3 m wide perform well for ACH.

- Options 4 with light well closer together have lower mean indoor temperature.

- Options 1 and 3, with more depth and a single court of light, have a lower mean ACH.

Figure 12

Fig. 12. Wind velocity filled contours pattern in top floor plan view on January 5th 9 am for wind direction from South East and wind speed of 1.23 m/s.

These findings underscore the importance of light well geometry, positioning, spacing, and depth as interrelated parameters that must be carefully balanced to enhance natural ventilation. While certain configurations may optimize air change rates, achieving thermal comfort in hot-humid climates likely requires a combination of design strategies beyond passive ventilation alone.

The findings of this study align with and extend previous research on the role of light wells in enhancing daylighting and natural ventilation performance. For instance, the superior performance of southern-oriented light wells supports earlier conclusions by Kristl and Krainer [1], who found orientation to be a critical factor in maximizing daylight availability. Similarly, the effectiveness of double light well configurations, particularly those arranged perpendicularly, is consistent with the work of Alah et al. [7], who demonstrated that geometric variation and spatial distribution significantly affect environmental performance. This study adds to the existing body of knowledge by employing a generative design approach, which enabled the exploration of thousands of light-well configurations based on real climate data. Unlike previous studies that relied on static models or limited variations, the use of Ladybug, Honeybee, and Galapagos facilitated an optimization process that revealed a critical volume ratio threshold ( 20%) for achieving acceptable daylight and ventilation levels in deep-plan buildings. This threshold not only corroborates earlier work (e.g., Muhsin et al. [17]) but also provides quantitative design guidance for both new construction and retrofitting projects in heritage or high-density urban zones.

In this study, the interaction between daylighting and natural ventilation in deep-plan buildings was investigated using generative design and environmental simulation techniques. The results indicate that the orientation, light well configuration, and well size significantly affect both daylight availability and ventilation performance. However, this study has several limitations. The CFD analysis was conducted solely for south-facing configurations, selected for optimal daylighting outcomes, which may not represent performance across all orientations. The Daylight and ventilation simulations were based on open floor plans without internal partitions. Although this simplification facilitates comparative analysis, it does not account for the complexities of typical interior layouts. The results should be regarded as indicative rather than definitive, offering guidance for early-stage design decisions related to light well sizing and positioning rather than final design solutions. Validating the simulation results through field measurements was not feasible owing to difficulties in accessing comparable traditional deep-plan buildings, leaving empirical confirmation of the findings for future investigation. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into passive design strategies for enhancing indoor environmental quality in dense urban and traditional contexts. Future research should encompass a broader range of orientations, incorporate internal spatial divisions, and explore opportunities for real-world validation to enhance the applicability of the results.

5. Conclusion

In this study, a pattern of double light wells arranged perpendicularly has been proposed to enhance daylighting and natural ventilation for a typical base case plot size of 6 x 20 meters. The natural ventilation performance of these light wells has also been assessed. The study's findings indicate that double rectangular light wells of 3.5 x 2.5 meters in option 5 and 6 and a random size in option 7 provide UDI of more than 50% of the floor area. These rectangular light wells were chosen for the natural ventilation study due to their satisfactory daylighting performance. The results suggest that incorporating a light well with a volume exceeding 20% of the total building volume is a critical design criterion for optimizing daylighting and ventilation in deep-plan configurations. This volumetric threshold serves as a key performance indicator for future generative design studies and may inform passive design strategies in similar climatic and spatial contexts.

The study recommends adopting a minimum 20% light well volume ratio as a design benchmark for enhancing passive environmental performance in heritage-sensitive areas, applicable to both existing and newly proposed buildings. Under these evolving scenarios, the recommended light-well dimensions and volume ratio continued to perform effectively. However, in this study method to validation from field data for daylighting and natural ventilation performance for the given context was not possible, which could be for future extended research. This indicates that the proposed design strategy is not only effective for current built forms but is also scalable and adaptable to future densification patterns. Consequently, this study's recommendations can inform policy and building guidelines for sustainable urban development in tropical heritage cities.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

C. Chockalingam: Conceptualisation, methodology, software, formal analysis original writing and overall editing & administration of the study. C. Balakrishnan: Resources, validation, visualisations, language checking and review.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Z. Kristl, A. Krainer, Light wells in residential building as a complementary daylight source, Solar Energy 65:3 (1999) 197-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-092X(98)00127-3

- V. Garcia Hansen, I. Edmonds, Natural illumination of deep-plan office buildings : light pipe strategies, in: ISES Solar World Congress 2003, Göteborg, Sweden, 2003, pp.14-19.

- D. Etheridge, Natural Ventilation of Buildings: Theory, Measurement and Design, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. London, UK, 2012.

- L. Moosavi & N. Mahyuddin, N. Ab Ghafar, M.A. Ismail, Thermal performance of atria: An overview of natural ventilation effective designs, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 34 (2014) 654-670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.02.035

- S.D. Ray, N.W. Gong, L.R. Glicksman, J.A. Paradiso, Experimental characterization of full-scale naturally ventilated atrium and validation of CFD simulations, Energy and Buildings, 69 (2014) 285-291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.11.018

- H. Kotani, M. Narasakia, R. Sato, T. Yamanaka, Environmental assessment of light well in high-rise apartment building, Building and Environment, 38:2 (2003) 283-289. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1323(02)00033-1

- A. A. Ahadi, M. R. Saghafi, M.Tahbaz, The optimization of light-wells with integrating daylight and stack natural ventilation systems in deep-plan residential buildings: A case study of Tehran, Journal of Building Engineering, 18 (2018) 220-244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2018.03.016

- Y. Su , H. Han, S. B. Riffat, N. Patel, Evaluation of a lightwell design for multi‐storey buildings, International journal of energy research, 34:5 (2010) 387-392. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.1651

- J. Du , S. Sharples, The variation of daylight levels across atrium walls: Reflectance distribution and well geometry effects under overcast sky conditions, Solar Energy, 85:9 (2011) 2085-2100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2011.05.015

- J. Yunus, S. S. Ahmad, A. Zain-Ahmed, Evaluating daylighting of glazed atrium spaces through physical scale model measurements under real tropical skies condition, in: Recent researches in energy environment entrepreneurship innovation, 2011, pp. 122-127.

- M. A. J. D. E. Leon, B. Lau, Optimum gradual glazing in atria for optimized daylight performance in adjacent spaces, in: 29th Conference on Passive-Low Energy Architecture conference - Sustainable Architecture for a Renewable Future, Munich, Germany, 2013.

- A. A. Freewan, A. A. Gharaibeh, M. M. Jamhawi, Improving daylight performance of light wells in residential buildings: Nourishing compact sustainable urban form, Sustainable Cities and Society, 13 (2014) 32-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2014.04.001

- A. A. Ahadi, M. R. Saghafi, M. Tahbaz, The study of effective factors in daylight performance of light-wells with dynamic daylight metrics in residential buildings, Solar Energy, 155 (2017) 679-697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2017.07.005

- H. Kotani, M. Narasakia, R. Sato, T. Yamanaka, Natural ventilation of light well in high-rise apartment building, Energy and Buildings, 35:4 (2003) 427-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7788(02)00166-4

- H. Kotani, M. Narasakia, R. Sato, T. Yamanaka, Stack effect in light well of high rise apartment building, International Symposium on Air Conditioning in High Rise Buildings, Shanghai, China, 1997, 628-633.

- T. G. Farea, Configuration of Horizontal Voids and Lightwell to Improve Natural Ventilation in High-rise Residential Buildings in Hot Humid Climate, Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 2014.

- F. Muhsin, W. F .M .Yusoff, M. F. Mohamed, A. R. Sapian, CFD modeling of natural ventilation in a void connected to the living units of multi-storey housing for thermal comfort, Energy and Buildings 144, (2017) 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.03.035

- S. Carlucci, F. Causone, F. De Rosa , L. Pagliano, A review of indices for assessing visual comfort with a view to their use in optimization processes to support building integrated design, Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 47 (2015) 1016-1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.03.062

- ECBC, Energy Conservation Building Code 2017, Bureau of Energy Efficiency Published by Bureau of Energy Efficiency New Delhi, India, 2017, Clause 4.2.3, Tables 4-1.

- Bureau of Indian Standards, National Building Code of India 2016, New Delhi: BIS, Part 8, Section 1 - Lighting and Ventilation, table 5.2.2.1, 35.

- D. P. Sari, Visualising daylight for designing optimum openings in tropical context, ARSNET 4:1, 2024, 72-85. https://doi.org/10.7454/arsnet.v4i1.87

- J. A. Ahmed, W. F. M Yusoff, M. F. Mohamed, Validation Field-Measured Data Through Design-Builder Simulation Software of Indoor Air Temperature in A Modern Residential Building in Erbil, Iraq, Instrumentation, Mesure, Metrologie, 24:2 (2025) 131. https://doi.org/10.18280/i2m.240204

- W. Köppen, Das geographische System der Klimate. Handbuch der Klimatologie, edited by Köppen Wladimir and Rudolf Publisher : Geiger, vol. 1, pt. C. Gebrüder Borntraeger, 1936.

- INTACH, Architecture heritage of Pondicherry-Tamil and French precincts, 2nd edition, Asia Urbs, France, 2020, pp. 99.

2383-8701/© 2025 The Author(s). Published by solarlits.com. This is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

HOME

HOME Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 8 Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure 11

Figure 11 Figure 12

Figure 12 Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14 Table 1

Table 1 Table 2

Table 2 Table 3

Table 3 Table 4

Table 4 Table 5

Table 5 Table 6

Table 6