Article Outline

2. Aim and State-of-the-art statement

4. Pre-study and the initial results

6. Results of dynamic-objects daylight simulation (post-prospecting)

7. Multi-objective optimization to ensure the reliability of third logic (the most cost-effective)

Declaration of competing interest

Figures and tables

Volume 12 Issue 1 pp. 69-90 • doi: 10.15627/jd.2025.5

Designing Adaptability Strategy to a Novel Kinetic Adaptive Façade (NKAF); Toward a Pioneering Method in Dynamic-objects Daylight Simulation (Post-Processing)

Ali Goharian,a Mohammadjavad Mahdavinejad,a,∗ Sana Ghazazani,b Seyed Morteza Hosseini,c Zahra Zamani,d Hossein Yavari,a Fereshteh Ghafarpoor,d Fataneh Shoghid

Author affiliations

a Compu-lyzer Architects Association, Department of Architecture, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

b School of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science & Technology, Tehran, Iran

c Department of Architecture, Design & Media Technology, Aalborg University Copenhagen, Denmark

d Department of Energy and Architecture, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

*Corresponding author.

ali.goharian@modares.ac.ir (A. Goharian)

mahdavinejad@modares.ac.ir (M. Mahdavinejad)

sana28gh@gmail.com (S. Ghazazani)

smho@create.aau.dk (S. Morteza Hosseini)

zahrazamanii@ut.ac.ir (Z. Zamani)

hossein_yavari@modares.ac.ir (H. Yavari)

ghaffarpoor@ut.ac.ir (F. Ghafarpoor)

shoghifattane@gmail.com (F. Shoghi)

History: Received 10 November 2024 | Revised 12 December 2024 | Accepted 25 December 2024 | Published online 8 February 2025

Copyright: © 2025 The Author(s). Published by solarlits.com. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Citation: Ali Goharian, Mohammadjavad Mahdavinejad, Sana Ghazazani, Seyed Morteza Hosseini, Zahra Zamani, Hossein Yavari, Fereshteh Ghafarpoor, Fataneh Shoghid, Designing Adaptability Strategy to a Novel Kinetic Adaptive Façade (NKAF); Toward a Pioneering Method in Dynamic-objects Daylight Simulation (Post-Processing), Journal of Daylighting 12 (2025) 69-90. https://dx.doi.org/10.15627/jd.2025.5

Figures and tables

Abstract

The design and evaluation of adaptive facades (AFs) have become increasingly complex due to advancements in morphology, control strategies, and adaptability techniques. This study introduces a Novel Kinetic Adaptive Facade (NKAF) incorporating photovoltaic (PV) panels and Plexiglas to enhance daylight and view performance in office buildings. The research focuses on two objectives: (1) the innovative design of the NKAF, and (2) dynamic assessment of its daylight performance using advanced simulation methodologies. Annual daylight simulations, conducted with Radiance and a cutting-edge dynamic-objects workflow, evaluated three adaptability strategies: blocking direct sunlight, tracking solar trajectories, and minimizing facade movement. Results indicate that the fully dynamic sun-blocking logic significantly improved useful daylight illuminance (UDI 100-3000 lux) from 49% to 90%. Additionally, post-processing with NSGA-II multi-objective optimization provided an optimal framework for annual performance, effectively balancing multiple design goals. This novel methodology enables the simulation of dynamic environments and facades, addressing a key gap in previous daylighting research.

Keywords

Compu-lyzer Architecture, Dynamic-objects daylight simulation, daylight performance, Kinetic adaptive façade

Nomenclature

Abbreviation

| AFs | Adaptive Facades |

| NKAF | Novel Kinetic Adaptive Façade |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

1. Introduction

The long-term viability of buildings is affected by three difficult factors: promoting occupant health and indoor environmental quality, decreasing the energy used by the building, and minimizing the building's negative impacts on the environment [1]. Studies examining lighting conditions in office environments demonstrate clear links between the amounts of light at eye level (illuminance) [2] and health measures in employees [3]. The studies find that daylight exposure affects productivity, physical health, and job satisfaction among office workers. Specifically, they show that offices with ample natural light lead to higher productivity, better health outcomes, and increased employee satisfaction compared to poorly lit offices [4]. In summary, the level of lighting, especially from natural sources, has a significant influence on employees' productivity, health status, and satisfaction in office settings.

The development and use of innovative building envelope designs that are interactive, adaptable, and reactive could enhance daylighting in buildings. Improved daylighting would in turn bolster the sustainability of these buildings. Specifically, new building envelope systems that can dynamically respond to environmental conditions and occupant needs may optimize daylight penetration and distribution. Examples could include intelligent glazing, movable shading systems, and integrated photovoltaics. By implementing these types of advanced facades that automatically adjust daylight illumination, buildings can become more energy efficient and provide optimal visual comfort for occupants. In summary, interactive building envelopes represent a promising approach for sustainably improving daylight utilization in buildings [5-7].

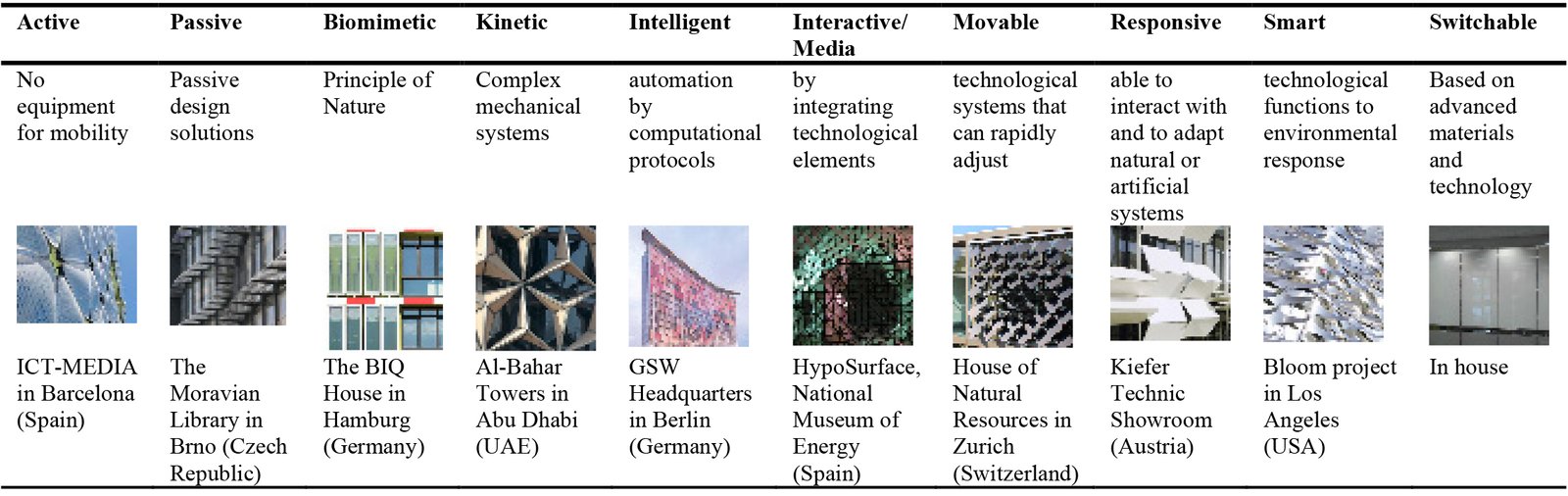

Based on the sources of Web of Science, Scopus, and other publications in Green files, many studies have been conducted in the past years regarding the AFs and these studies have been expanded in the field of experiment, simulation, and numerical calculations. Due to this volume of studies, the classification and terminology of AFs have been greatly expanded by authors, and finally, there is no precise limit between all types of AFs, and definitions and classifications are always ambiguous. Although A. Tabadkani has made a lot of effort to classify the types of AFs, still there are some ambiguities [8]. Based on Tabadkani’s classification, ten categories are distinguished in approaching the design and shown in Table 1.

However, there are generally common expectations between all adaptive and kinetic facades. Therefore, according to the European COST Action TU1403 Adaptive Façades Network (2014-2018), kinetic or adaptive building facades can have a significant impact on the performance needs in three key areas: occupant satisfaction, energy efficiency, and environmental sustainability [9]. The integrated design of AFs, especially the kinetic or movable adaptive façade (because of requiring advanced technology and evaluations), involves a series of integrated scientific-practical processes toward the goal or goals of AF’s design [10]. AFs, especially when mobility with different goals plays the main role, and a range of different disciplines including design [11], electronics [12], mechatronics [13], environmental performance evaluation [14], computational modeling [15], and mathematics [16] can be involved in the design process; As a result, the process of designing an AF is an interdisciplinary concern. Therefore, most trends strive with the ultimate goal of improving daylight performance vs artificial light, thermal and visual performance of occupants, and reducing energy consumption.

With a systematic search, it is possible to witness the wide range of studies on kinetic adaptive facades in recent years, studies investigating the goals of improving kinetic adaptive facades are being conducted, focusing separately on their main performance aspects, although overall performance improvement is considered. For example, with separate approaches to daylighting [17], thermal-visual comfort [18], and energy efficiency [19]. Such approaches can solve gaps and problems in depth, although experts should regard the logic and presuppositions related to other approaches. Adaptability in AFs means the facade can automatically adjust its features, configurations, characteristics, or actions over time. This adjustment happens in response to changing building needs or external environmental circumstances. The time frame based on the concept can have different logics and configuration changes can occur on a short time scale.

The response time scale is diverse and dependent on expected human comfort. These time frames can range from seconds to entire seasons [20,9,21]. For example, some shading systems may adjust on an hourly basis while switchable glazing [22] may change over the course of days or months. The rate of adaptation can vary greatly but the changes are intended to be observable over the life of the building. The timescale can be categorized as follows:

- Seconds - Facades may change configuration randomly in response to fluctuations like wind.

- Minutes - Facades may alter transparency as daylight and clouds change over minutes.

- Hours - Facades may track the sun's position across the sky over hours.

- Diurnal - Facade changes can match daily occupancy patterns.

- Seasons - Facades adapt to different ambient conditions across the seasons.

- Local-patterns – Facades adapt efficiently to occupant’s position or optimized-environmental analysis

The control strategies and dynamic operation of daylighting in the system of the AF are subject to the logic and plans of adaptability (time frame). In other words, determining the type of control system will happen after the logic of adaptability, which is influenced by improved comfort, occupant interaction, and smart automation among personalised control and service-driven [20]. With the general division of control strategies into open-loop and closed-loop conventionally for the AF with the local-pattern, the open-loop system can be used regularly, on the other hand, it can be used to optimum the indoor environmental conditions and reduce the error of sensors’ conflict [23]. It can be improved from the closed loop strategy by getting feedback (by types of sensors [24]).

1.1. Functionality of kinetic AFs and dynamic PV facades

Kinetic adaptive facades are complex mechanical systems that utilize motions like displacing, sliding, expanding, folding, or transforming to achieve variable geometries and mobility [25]. Kinetic facades differ from other dynamic facades in their priority to respond to outdoor environmental conditions efficiently, rather than simply reacting to indoor conditions or moving for visual effect. The key functionality of kinetic facades is adapting the exterior facade to optimize it based on external climate, sunlight, ventilation requirements, etc. To enable this, kinetic facades incorporate effective mechanical systems and controls that trigger facade motion based on sensor data from the outside environment. Therefore, the driving force behind the motion capabilities of kinetic facades is responsively modulating the building exterior to outdoor conditions, not creating motion as a novelty for interior spatial effect. The focus is on having the kinetic movements actively adapt the facade’s configuration in response to the specific external variables at any given time.

Dynamic photovoltaic facades that can respond to outside conditions can save more energy than fixed shading devices. The mechanics used to move adaptive façade/shading systems could easily integrate with mechanics required for solar tracking photovoltaic systems that are part of building facades [26]. A major issue with many photovoltaic system installations, especially tracking systems and those tightly incorporated into buildings, is the shading of PV modules by other modules or nearby objects. Shading of modules can cause electrical mismatch losses, overheating, reducing power output, and negatively influencing system reliability [27]. Some proposed solutions to lessen these negative impacts include optimally arranging PV modules and controlling the tracker movement to avoid shading [28].

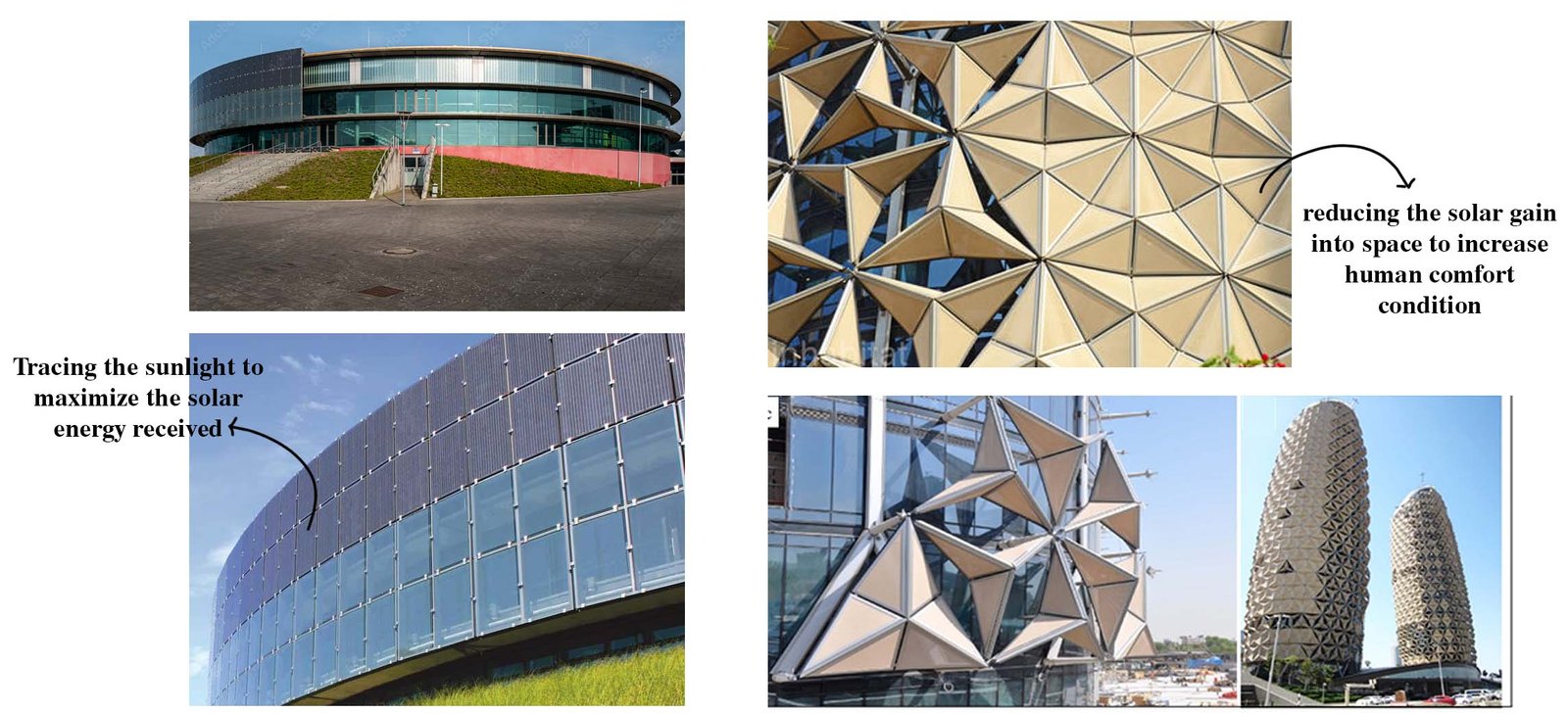

In general, when integrated photovoltaic systems are used on dynamic facades, in order to maximize the potential of receiving radiation, all design goals, especially from the point of view of morphology, are directed towards the facade-sun position interaction. In other words, the interaction between the facade and the sun position is prioritized among the goals. Figure 1 demonstrates a comparatively dynamic adaptive façade (EWE Arena in Oldenburg (Germany) [29] and kinetic adaptive façade ((Middle) Al-Bahar Towers in Abu Dhabi. As it is known, in the classification of some types of AFs, there are faint borders, especially if innovative ideas cause them to be combined. For example, the kinetic facade can be covered with photovoltaic cells [30], although dynamic photovoltaic facades have different definitions according to their purpose. Kinetic adaptive facades utilize a wide range of motions (sliding, folding, pivoting, etc.) to modulate sunlight, ventilation, views, aesthetics, etc. Dynamic photovoltaic facades specifically feature movable photovoltaic panels/louvers to optimize solar exposure for electricity generation. Dynamic photovoltaic façades concentrate specifically on moving photovoltaic panels and louvers in order to optimize solar exposure. In this present paper, the focus is on the combination of dynamic PV façade with kinetic adaptive façade called NKAF.

Figure 1

Fig. 1. Comparatively the functionality of the dynamic adaptive façade (EWE Arena in Oldenburg (Germany) and kinetic adaptive façade ((Middle) Al-Bahar Towers in Abu Dhabi.

2. Aim and State-of-the-art statement

AF's design is a multi-function and multi-purpose design that should control the outdoor environmental conditions in order to improve the indoor environment [31]. Allowing or obstructing incident light is always the challenge of a kinetic adaptive facade, now if the logic of the sun position is the main concern of the facade design; the design concept will be pushed towards a non-conventional kinetic adaptive facade. Maximizing the efficiency of daylight and controlling overheating and glare simultaneously, the solution of which can be matching the covering part of the facade with the coordination of the sun. This concept may [32] or may not [30] be directly related to the occupant's position.

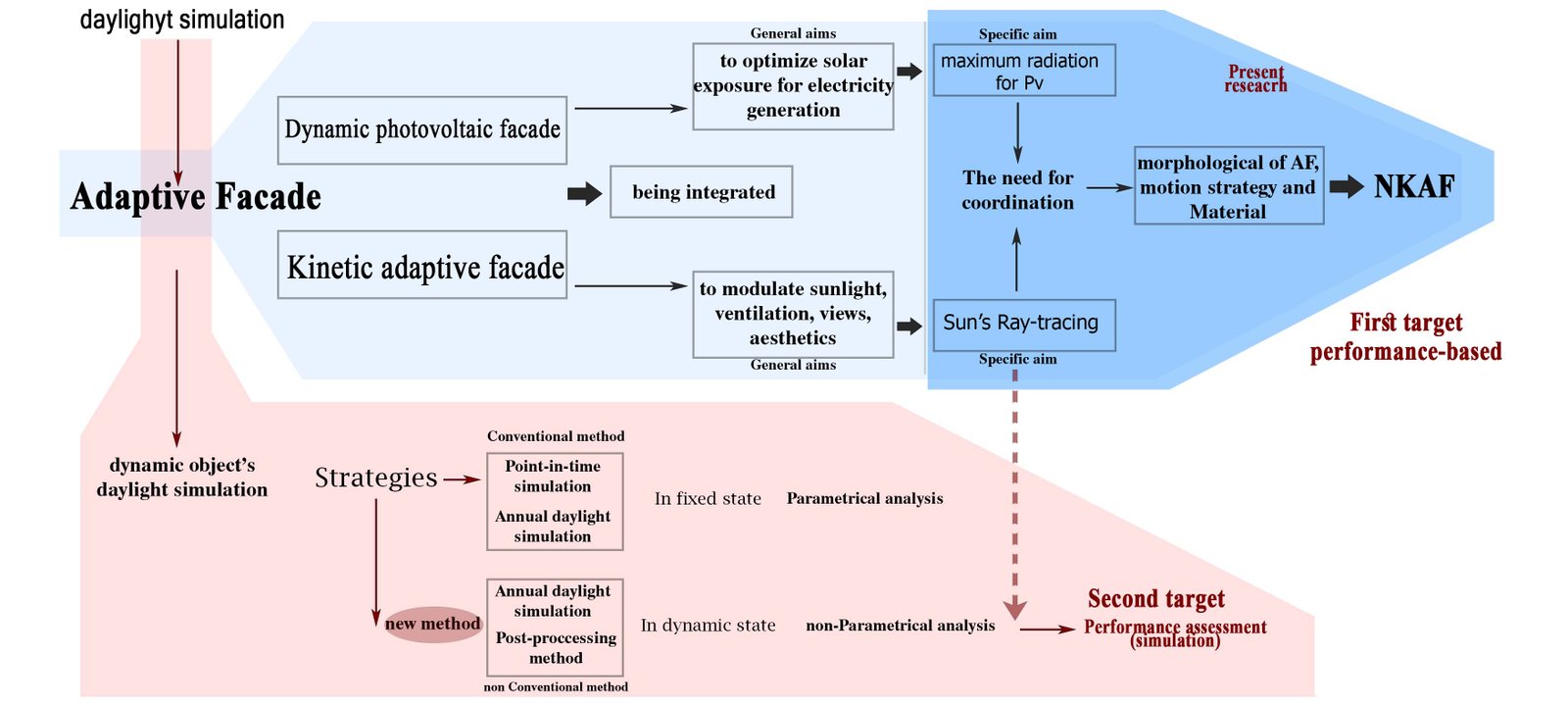

Combining and integrating different types of adaptive dynamic facades is not an easy task due to their diverse functions and objectives. In this study, we seek to create an integration between these facades that includes two different functions each: one of the facades is more concerned with the external conditions and is known as the photovoltaic dynamic facade, and the other is designed to improve the performance of the interior environment and is known as the kinetic facade. Research [33,34] has sought to respond to the challenges of human comfort and energy consumption optimization with an approach based on the interaction between the position of the sun and the facade. Also, a study conducted by [35] shows that trying to track the sun's rays maximizes the use of the received radiation which is converted into electrical energy by photovoltaic cells. Figure 2 shows the goals and gaps of this research in two groups (targets). As is clear, the Integration and combination of the two functions of AFs have different purposes. In other words, the main goal in dynamic photovoltaic facades is to maximize the amount of radiation falling on the panels, but the kinetic adaptive facade emphasizes improving the indoor condition and in some respects the occupants. Form finding, mobility strategies, and material selection can be effective on the internalized efficiency of an AF, which in this research, NKAF is extracted; a kinetic facade integrated with PV considering the material in order to the objectives of shading and the view quality. The movement strategy of the model is adopted with a few changes from a non-reference image available on online design-related websites.

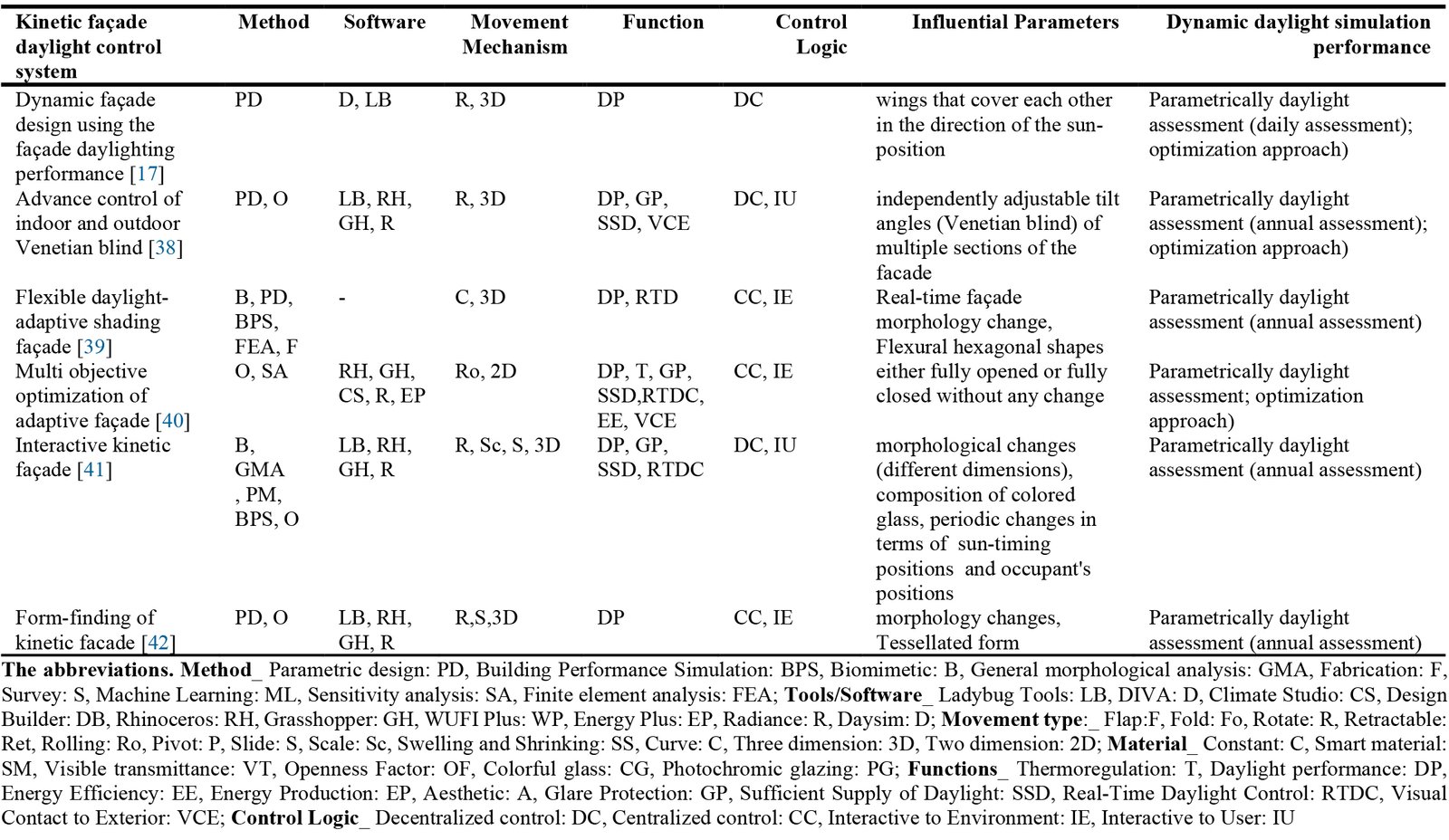

In the present study, daylighting behavior is the focus of the research. The second part (second target) of this research, after the conventional analyses in the field of daylight, responds to a new method (post-processing) in dealing with the analysis of dynamic objects [36]. One of the most critical challenges of dynamic facades in the field of daylight simulation is the annual dynamic-object simulation, which inevitably leads most researchers to parametric simulations (Either dynamic-environment to fixed facade, or in real-time assumptions to point-in-time simulation). Especially in daylight simulations, not only the application of control strategies but also the design of adaptability strategies fail. Daylight harvesting by EMS [37] works in the field of dynamic facades but fails in the face of non-conventional facades. Table 2 reviews recent studies in the field of dynamic facade assessments in terms of simulation approach. A lack can be seen in all these studies; According to conventional simulation, either the environment is dynamic (annual simulation) and the facade is in one state, or the states are changed parametrically at a point-in-time (annual simulation does not happen with the facade mobility schedule) [17,38-42]. Optimistically, the present study presents a cutting-edge method for simulating both dynamic-environment and dynamic-facade in the simulation of daylight by Radiance software by a post-processing approach.

Table 2

Table 2. Review on kinetic façade characteristics concerning pioneering daylight simulation through adaptability movement logic.

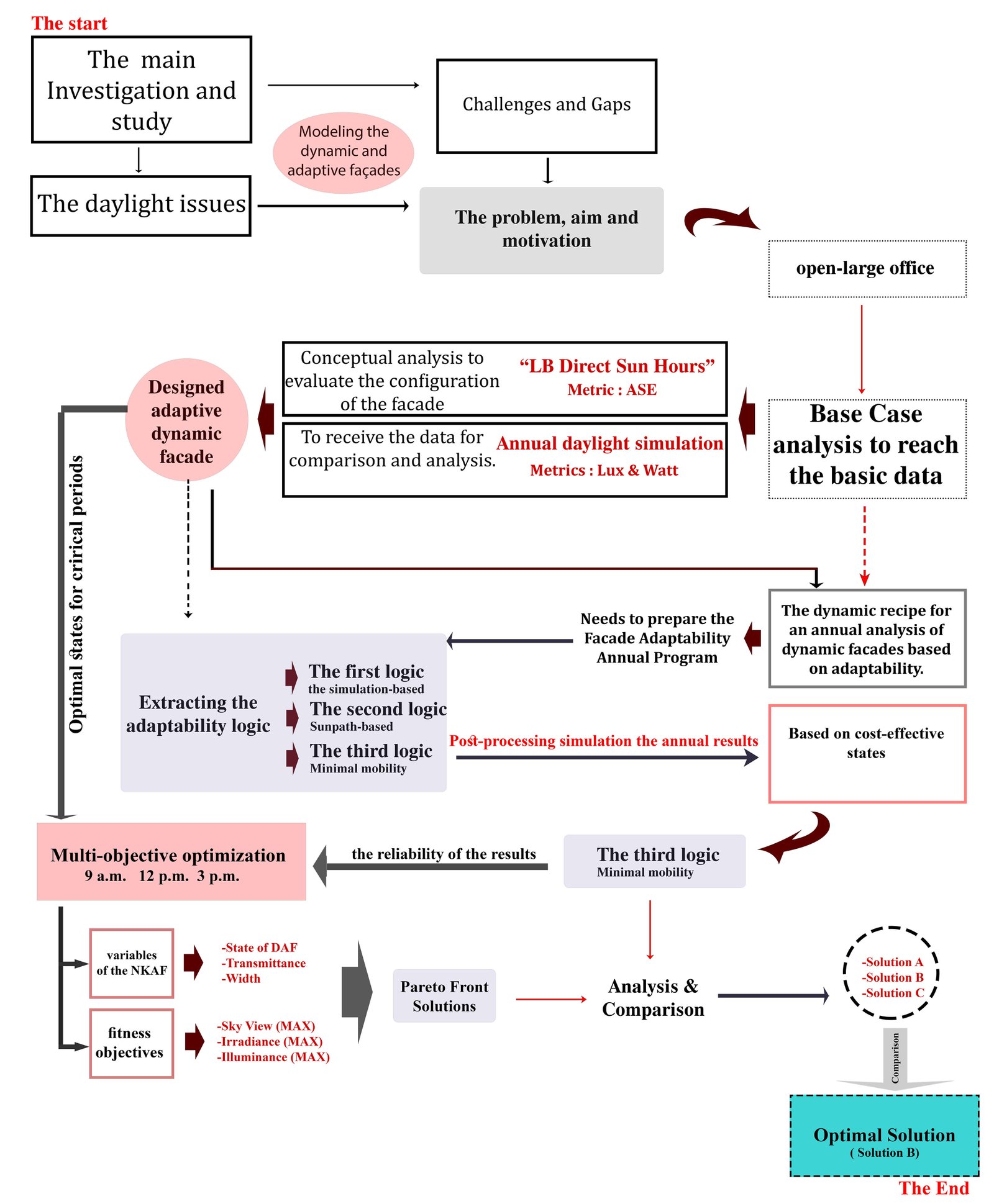

3. Methodology

3.1. The process of the research

This research, first, started with studies related to dynamic adaptive facades through daylight and daylight simulation performance for dynamic objects and according to the existing gaps and problems, the early-stage design was started. Figure 3 summarizes the research methodology. Initially, the ASE index validation guided the transition to the next stage, focused on evaluating daylight efficiency. The physically fixed model was adapted into an advanced simulation workflow, while the NKAF was optimized to ensure result reliability. Finally, daylight simulation comparisons identified and validated the optimal solution.

In general, the methodology of this research is based on two main workflows: post-processing and optimization. One of the significant problems in the analysis and evaluation of moving objects that deal with daylight is always a lack of practicality in this field. In this research, after the modeling, the design was fully investigated through dynamic-daylight simulations that was adapted to the adaptability strategies (program). This program is implemented to be able to evaluate the performance of the dynamic facade on an annual basis; however, it should be noted that this is only an annual program and does not provide the best mobility rhythm.

To overcome this lack, the optimization process is considered the second important part of this research to verify the accuracy and efficiency of the adaptability strategies. In other words, if the facade positioning conditions are examined with respect to three basic criteria, namely, the radiation on the panels as a source of electricity, the view outside for the users, and the amount of useful illumination, can it still confirm the accuracy and efficiency of the proposed adaptive program? In this research, the third logic for adaptability strategy was optimized based on a cost-effective solution.

3.2. Software

The Grasshopper plug-in for Rhino facilitates parametric modeling by enabling the design and arrangement of algorithms. Since 2014, the Honeybee and Ladybug plug-ins (legacy versions) have been developed within Grasshopper to simulate building physics [43]. These plug-ins analyze various environmental factors, measuring indicators such as light, energy, and thermal-visual comfort. Ladybug processes geometry and weather data and transfers it to Honeybee, which contains components for daylight and energy simulations. Essentially, Honeybee and Ladybug serve as interfaces for software such as EnergyPlus, OpenStudio, Radiance, Daysim, Therm, and LBNL Window. Specifically, Daysim and Radiance are used for daylight simulations, while EnergyPlus and OpenStudio handle energy simulations [44].

Despite their widespread use, the legacy versions of Honeybee and Ladybug have limitations, including accuracy issues and long runtimes. However, since 2019, an improved version called Ladybug Tools (LBT) has addressed these challenges, offering better accuracy and significantly faster performance [45]. This study utilized LBT version 1.6.0 from Rhino4food. In summary, Grasshopper facilitates parametric modeling, while the Ladybug and Honeybee plug-ins leverage external software to simulate lighting and energy use. The new LBT version has improved the process with enhanced accuracy and speed.

3.3. The reference model and the NKAF description

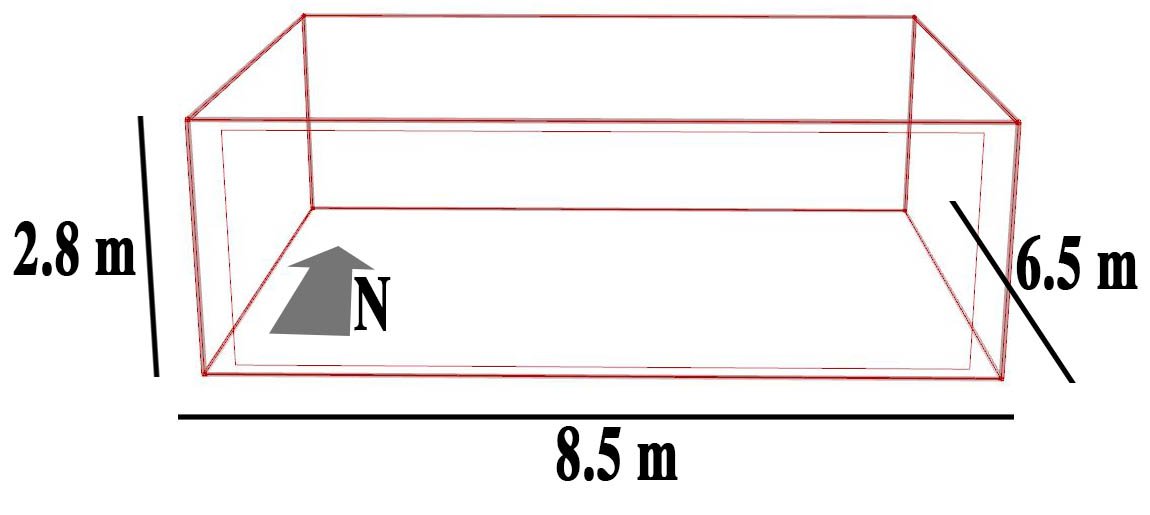

3.3.1 Reference model

The location of this study has been chosen in Tehran with hot and dry climate classifications in terms of Koppen categories [46] and the weather data is adopted from Energy Plus Weather (Epw) from an online website [47]. Modern office buildings prioritize open, flexible spaces with ample natural light, often featuring large windows and few interior walls or divisions. This research has chosen office space as the reference model. The reference model for this research is determined based on the open office space and the dimensions and sizes are adapted based on the available per capita.

According to Dimension's website, “The customary range for North American office standards [48] is 150-175 square feet (14-16.25 sq. m) of space per employee. In recent years, this average has replaced the previously common range of 200-250 square feet (18.58-23.23 sq. m). Ultimately, the total amount of space needed to accommodate a business influences the range of space per person. For example, startups and tech companies often adopt open-plan layouts, where the range is typically 100-150 square feet (9.30-14 sq. m) per employee. Finally, on a per capita basis, the maximum amount of space (14 square meters) is allocated for four desks (4 occupants), equating to 14 square meters per person.

Figure 4 illustrates the reference model. However, this research focuses on the performance of the NKAF, and the per capita space allocation does not significantly affect the outcomes in this context.

3.3.2. The NKAF

3.3.2.1. The Computational design

First of all, it should be defined that the NKAF consists of 17 two-piece panels. The upper part of each panel is installed with a photovoltaic cell, which provides shading in the space [49], and the lower part is made of translucent Plexiglass panels [50] to ensure optimal daylight quality and visibility. Due to the folding of the pieces over each other, a non-translucent (opaque) fabric material [51] is placed between the panels (Fig. 5).

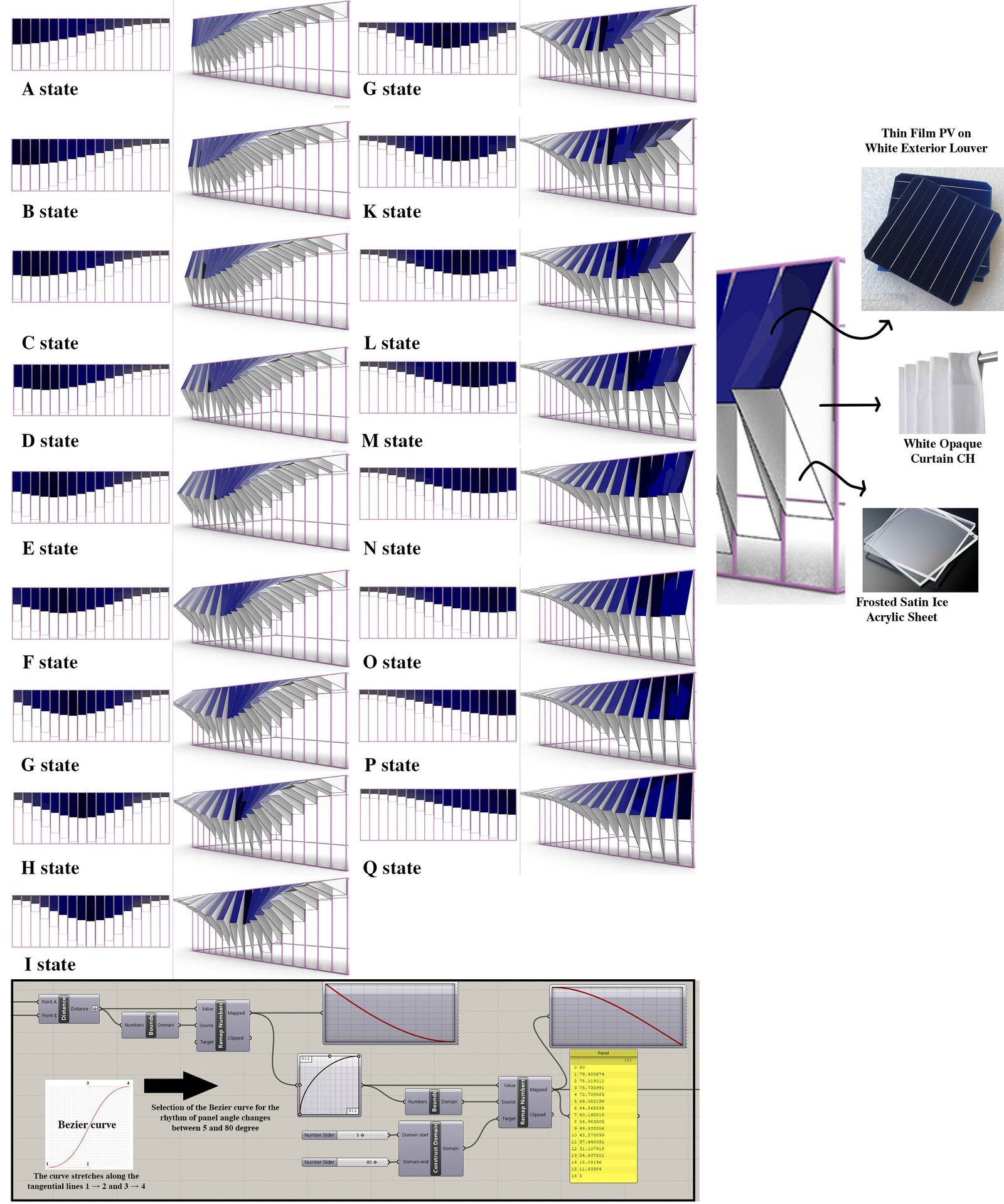

Figure 5

Fig. 5. The NKAF design and movement computation logic. The NKAF consists of 17 two-piece panels, the upper part of which is installed with a photovoltaic cell and causes shading in the space, and the lower part is made of Plexiglas panels (translucent) to provide the maximum quality of view and daylight sufficient. Due to the folding of the pieces on each other, there is fabric material between the panels (sides) and it is not translucent (opaque).

To realize the idea and motivation of this research, the NKAF computational design was developed by producing panels in the same direction and rotating them according to a set of angles with rhythmic variations. Algorithms were written using Grasshopper components. The most important aspect of the NKAF computational design is the set of panel angles, which are defined within a range from zero to one to determine rhythms between 5 and 80 degrees (the maximum and minimum angles of the panels). This computational pattern can be programmed into the NKAF actuators. This operation was carried out using the Graph Mapper component.

The Graph Mapper component in Grasshopper [52] is a powerful tool that enables you to map one set of values to another using a curve. The component has two inputs: one for the domain of the input values and another for the domain of the output values. The curve is used to map the input values to the output values. To use it, input your values on the X-axis (the lower side of the component), and they will be mapped using the curve onto the Y-axis (the left side of the component). You can set the interval that each side represents by double-clicking on the component. Additionally, you can choose from five different functions: double Bezier, arc, sigmoid, polyline, and interpolated. By changing a variable in the set of panels (17 two-piece panels), the range changes, causing the rhythmic movement of the NKAF. The NKAF is planned in 17 different states. As shown in Fig. 5, these states range from state A (completely inclined towards the west) to state Q (completely inclined towards the east).

3.3.2.1. The technical aspects

The façade depicts a unique structure made up of paired panels that move vertically and in a sliding manner. The main structure of the façade consists of an overall frame that is designed as a lattice in the vertical direction and operates independently of the main structure of the building, so that in fact this façade is known as a second skin that gives the building a modern appearance. Each of the frame grids in this design acts as a rail and allows the movement of paired panels that move and fold inside the frame independently. These panels are connected to each other at one edge and this hinge connection allows them to move easily and with a smooth and fluid operation. Also, on the other hand, these panels are defined by the use of a fabric that creates an opaque yet flexible wall, to enable the panels to move freely while integrating functionality into the facade. This design not only provides functional aspects but also pays attention to modular assembly and construction.

3.4. The General Simulation setup and material

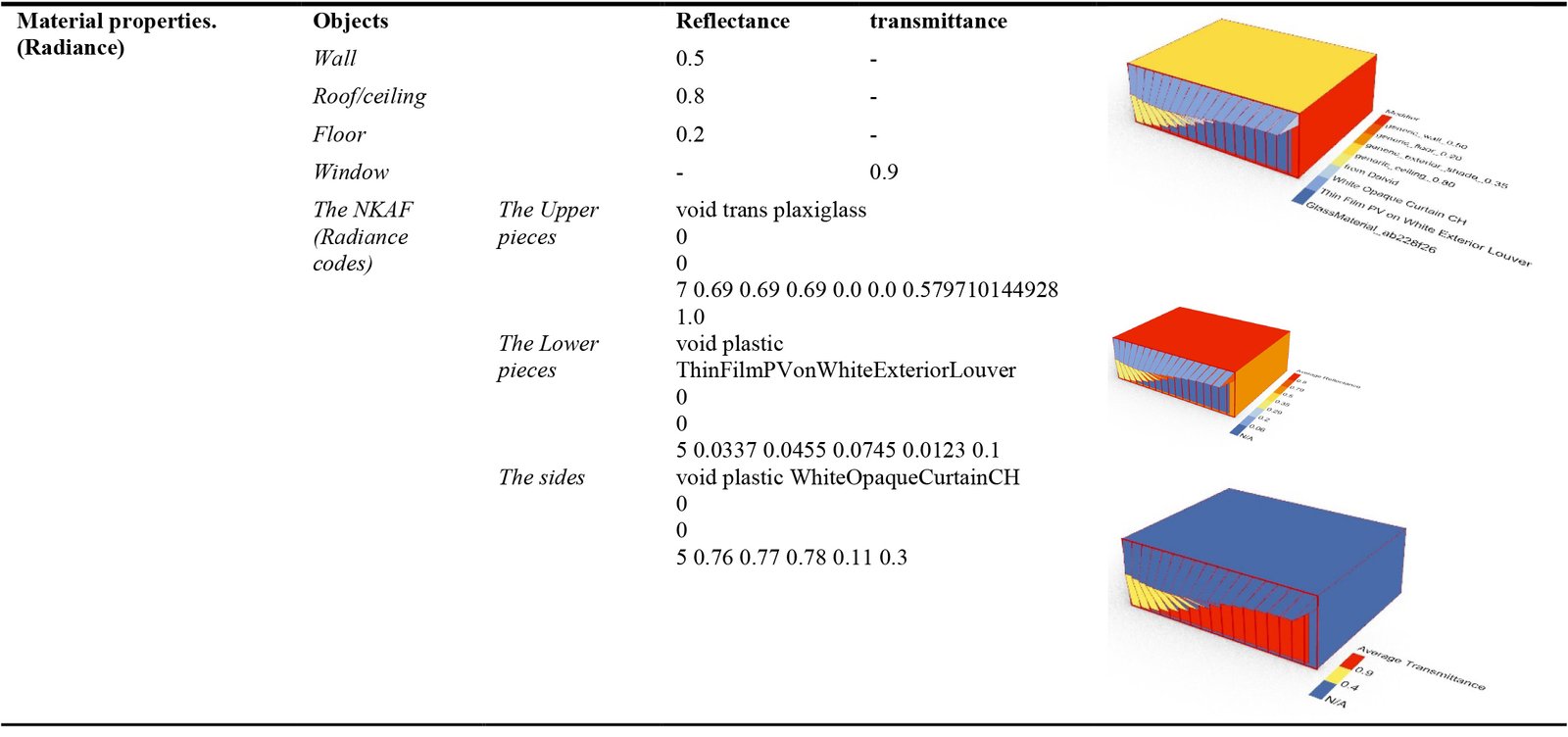

Even though the study's model has fixed requirements, it was nonetheless modeled in the Grasshopper environment to integrate with Ladybug Tools algorithms. The model, derived from the Honeybee library, was prepared using OpenStudio software after assigning the EPW file. To investigate daylight performance consistently, both in terms of direct ray analysis and annual daylight efficiency, common algorithms within Honeybee were employed. These algorithms transfer all settings—including geometry, materials (Table 3), and simulation recipes—to the Radiance engine for running.

All geometries are statically transferred in one state to the desired recipe, and the simulations are executed in Radiance. Thus, in this workflow, dynamic objects cannot be directly analyzed and are instead analyzed parametrically through variable adjustments. The workplane for simulation was established based on the LEED standard height of 85 cm from the floor, and the division of test points was set to 0.5 × 0.5 m to ensure sufficient accuracy, considering the dimensions of the space while maintaining optimal runtime.

3.5. dynamic-object daylight simulation workflow (post-processing)

The Radiance engine is recognized as one of the most reliable light simulation tools due to its unique and sophisticated syntax [53]. The input required for this simulation includes a description of the 3D surface geometry, materials, and light sources in a scene. Its dynamic annual daylight simulation capability allows for simulations using a dynamic sky, also referred to as climate-based daylight modeling (CBDM) [54].

Until now, the combined analysis of dynamic daylight and dynamic objects (geometry or Radiance materials) has primarily been performed using Daysim software [55]. However, because Daysim simulates each state separately and averages the results, its runtime becomes excessively long, making it inefficient for complex projects [56]. In the latest version of Ladybug Tools, the development team has introduced a significantly faster method within the plugin.

In Radiance, post-processing is essential for improving produced images' usability and interpretability, especially when it comes to architectural daylight performance studies. In order to determine how well a design works in natural daylight, users can statistically analyze important metrics including illuminance levels, contrasts, and color distributions using picture analysis. These studies become easier for non-technical stakeholders to understand when combined with visualization improvements like tone mapping and color correction, which guarantees that the findings are conveyed clearly and understandably.

Additionally, post-processing capabilities are enhanced by integrating Radiance outputs with other analytical tools like Grasshopper and Ladybug, allowing users to perform more complex studies and visualizations. Comprehensive reporting on daylight variations throughout the year is made possible by the integration of simulation data throughout time or across several scenarios. Furthermore, improvements in automated workflows, such as batch processing scripting, make handling big datasets easier, and the addition of improved measures, such Daylight Autonomy and Useful Daylight Illuminance, offers a more thorough understanding of daylighting performance. More involvement and comprehension of the design consequences are fostered by recent advancements in interactive visualizations, which give users even more control by enabling them to change parameters in real-time and see the direct effects on daylight conditions.

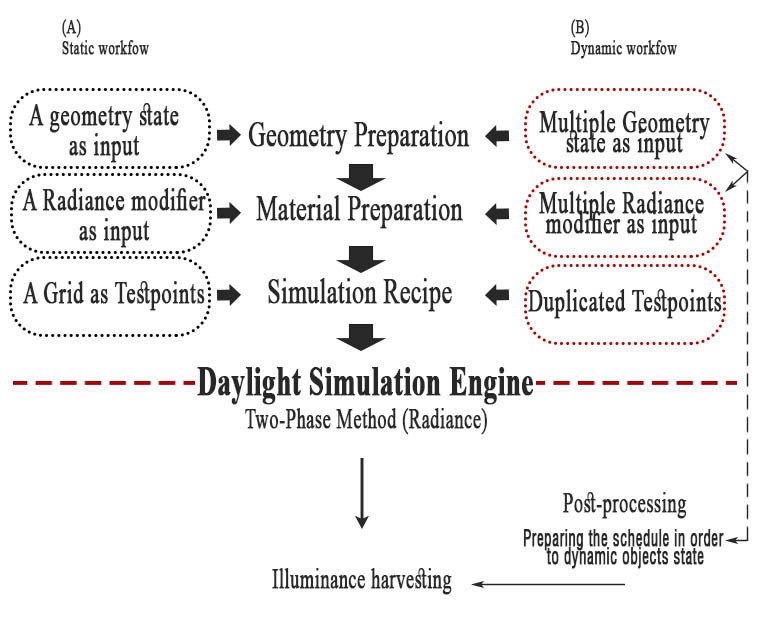

As shown in Fig. 6, this method processes dynamic objects by receiving inputs for all desired states during simulation pre-processing. The test points are duplicated to match the number of states, and each state is assigned a specific name as a required input during the pre-processing phase. Illuminance harvesting during post-processing allows results to be accessed using the designated names, meaning the results for any specific daylight state can be retrieved from the annual calculation data on an hourly basis. An annual mobility program is prepared in advance based on these state names and is defined as an input in the post-processing workflow. Using this computational algorithm, the movement of dynamic objects throughout the year is simulated, and the corresponding daylight calculations are obtained.

Figure 6

Fig. 6. Comparison between daylight simulations. (A) Shows daylight simulation workflow without any dynamic object (Sky is dynamic). (B) Shows dynamic-object daylight simulation (both sky and objects are dynamic).

In this study, the Facade Adaptability Annual Program refers to an annual schedule defining the movement patterns of dynamic objects for simulation purposes. While this schedule is typically annual, it can be adjusted based on the study period (e.g., seasonal changes). This program serves as an input for calculating daylight indicators but is only implemented after the simulation run is completed—that is, during the post-processing phase. For details on the program, refer to the Appendices.

3.6. Daylight Metrics

Two daylight metrics were utilized in this research: Annual Sunlight Exposure (ASE) and Useful Daylight Illuminance (UDI). ASE measures the percentage of an area receiving direct sunlight above a specified illuminance threshold (e.g., 1000 lux) for more than a set number of hours per year (e.g., 250 hours) [57,58]. It is important to note that ASE was originally developed as a glare indicator, addressing the question, "The daylight in this space is never too bright" [59].

In this study, the ASE metric is based on the LEED IEQ-Daylight LM-83 standard [57], with an acceptance threshold of less than 10%. This ensures that early-stage designs pose no risk of excessive brightness or glare discomfort for occupants. According to Mardaljevic and Nabil, the UDI metric measures how often, over a year, light levels on a surface fall within a range considered "useful" for the occupants of a space [60]. This dynamic metric reflects varying light levels and preferences, offering a comprehensive evaluation of indoor daylight quality. It is applicable to diverse spaces and design configurations, providing valuable insights into how daylight affects occupant comfort and productivity [60,61].

The premise of UDI is that low light levels necessitate the use of electric lighting, while excessively high light levels may interfere with specific tasks, prompting the use of shading. Thus, light is deemed "useful" only when it falls within a specific range of illuminance levels [60].

The UDI scheme categorizes daylight levels at each calculation point as follows [62,63]:

- UDI not achieved (UDI-n): Illuminance < 100 lux.

- UDI supplementary (UDI-s): Illuminance between 100 lux and 300 lux.

- UDI autonomous (UDI-a): Illuminance between 300 lux and 3,000 lux.

- UDI exceeded (UDI-x): Illuminance > 3,000 lux.

This range has primarily been defined for office spaces, typically between 100 lux and 3,000 lux [6]. Accordingly, in this study, the acceptable range of UDI was considered to be 100-3,000 lux.

In the preliminary investigation, we adopted a proactive strategy for glare evaluation, assessing glare levels before entering the more detailed analysis phase. Specifically, the management of glare risk employs early-stage design assessments based on the annual sunlight exposure (ASE) framework, with a particular emphasis on the LEED Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) Daylight credit as outlined in LM-83. Additionally, this study undertook an extensive year-long examination of adaptability mechanisms, integrating UDI indicators for both glare and darkness to guarantee the safety and comfort of the model. Our optimization methodology was distinctly organized around a one-hour interval, repeated three times, recognizing the limitations of annual daylight efficiency metrics in dynamic settings. To enhance the design effectively, we utilized a point-in-time approach, fine-tuning the illuminance levels between 100 and 3000 lux within the machine loops. This focused strategy was designed to address both underlit and overlit scenarios, ultimately aiming to minimize visual discomfort.

3.7. Spearman correlation coefficient to analyze how converging functions

As mentioned at first, Integrating or combining different types of kinetic adaptive facades is difficult due to their multi-functionality and different purposes. Such combination and integration regarded kinetic adaptive façade which means merging two different functions from each one (kinetic façade respects the outdoor condition and dynamic photovoltaic façade, the indoor). As a result, how these different functions converge, leads us to analyze the relevant outputs by Spearman correlation. In addition, analysis of the logic relative to each other is needed to investigate the simulation data. Thus, the Spearman correlation coefficient can compare and determine their relationships.

A correlation coefficient is always a number between 1 and -1. A correlation coefficient between 0 and 1 means a positive correlation, and the closer this coefficient is to 1, the stronger the correlation. A positive correlation means that as the score of one variable increases, the score of another variable also increases.

4. Pre-study and the initial results

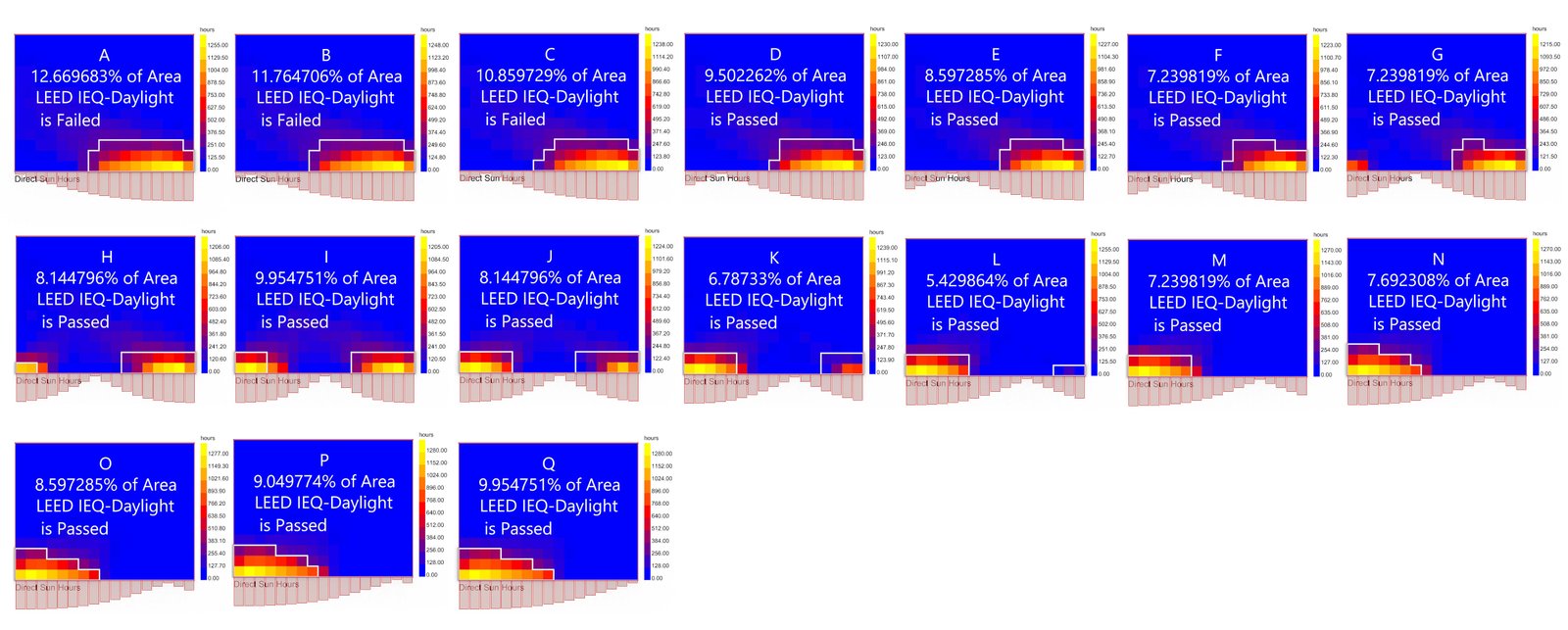

4.1. Estimation of the NKAF performance according to the LEED IEQ-Daylight; LM-83

When the intended target is outside the building and especially against the direct rays of the sun, the ASE metric can give an estimate of the relatively correct performance of the target based on the risk of glare. In this research, by applying the metric ASE based on LEED IEQ-Daylight LM-83, the algorithm of this estimation was written in the Ladybug plugin to the early stage of design and reaching the suitable configuration of the NKAF in terms of the daylighting. Figure 7 shows the amount of the ASE in space with the change of 17 the NKAF states by an algorithmic process. The dimensions, size, and movement characteristics (according to computational algorithms) of the NKAF determine the amount of direct rays passing through. In other words, the computational design follows the main function of a shade as a light blocker. According to the results of ASE based on LEED IEQ-Daylight, the NKAF performance is approximately correct. In fact, all situations have been passed by the LM-83 and the value of ASE is below 10%. Except for the three states A, B, and C, which is the covering part towards the west. Although the ASE values in these states are very close and below 12%. This method is a quick workflow to avoid bad and unpredictable performance.

Figure 7

Fig. 7. ASE based on LEED IEQ-Daylight LM-83, the algorithm of this estimation was written in the Ladybug plugin to the early stage of design and reaching the suitable physical properties of the NKAF in terms of direct sunbeams.

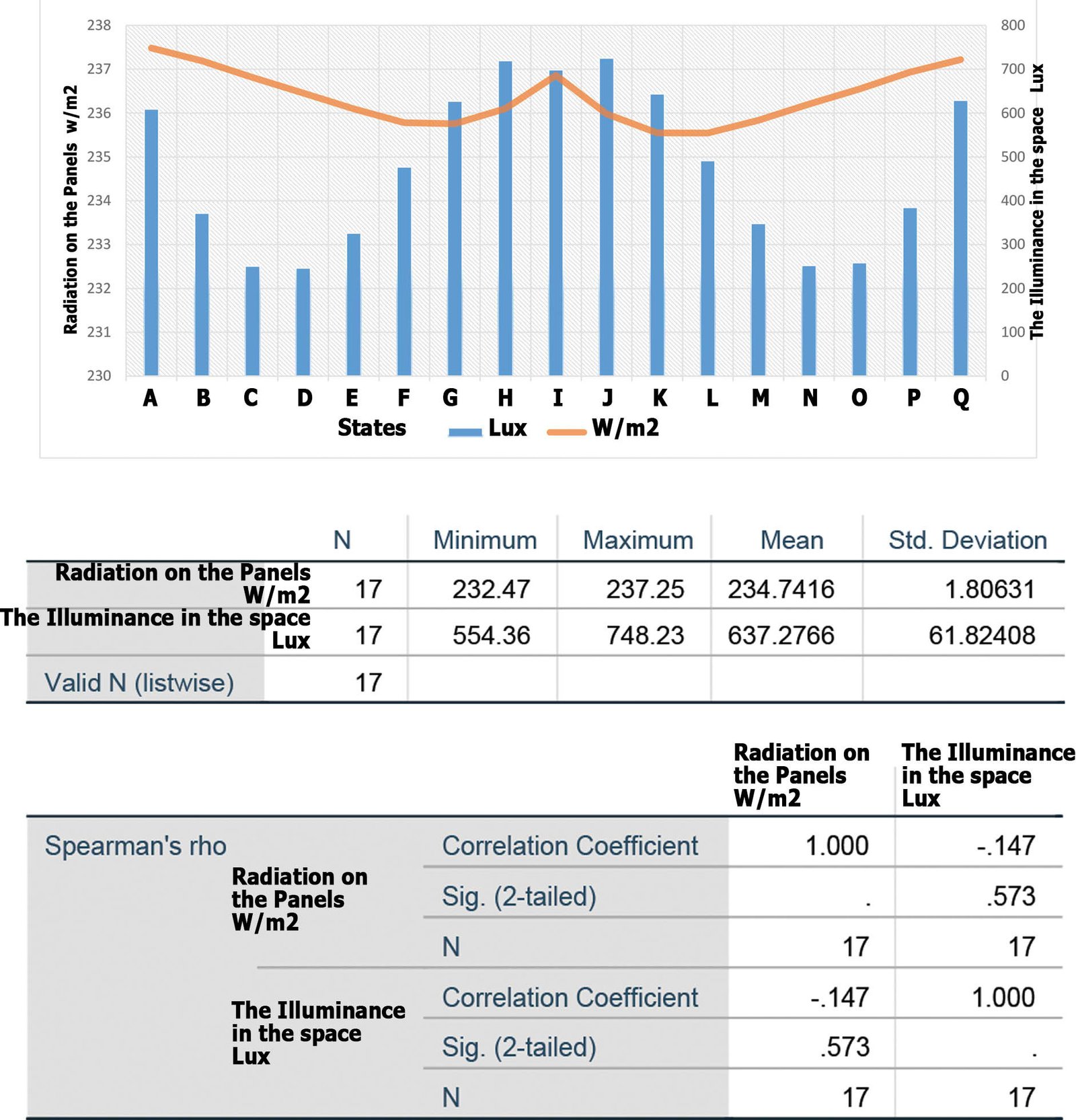

4.2. Investigating the radiation on the panels and illuminance in the space simultaneously

As discussed in the ideation of this research and its innovation, based on the panels being two pieces, photovoltaic cells are installed on the upper piece. Investigating the amount of solar radiation on the panels shows the production potential of electricity. Because the upper piece of the NKAF is for the installation of opaque photovoltaic cells and does not have any light-passing property, it has the nature of shading, and as a result, the simultaneous investigation of the amount of solar radiation on the panels and the amount of illumination entering the space can determine the performance of the NKAF changes in the determined range of mobility. The diagram in Fig. 4 shows the changes in the amount of solar radiation and illuminance during the change of the NKAF states. There is almost the maximum amount of solar radiation on the panels in three equal steps of the movement interval, and the maximum amount of illuminance in the space was recorded at the same points. This is an annual simulation, in other words, each state is simulated separately throughout the year; As a result, the maximum productivity is when the NKAF is either completely on the sides or exactly in the middle. According to Fig. 8 in the statistical description section, it can be seen that the standard deviation in solar radiation on the panels is very low and it is relatively high in the illuminance axis and is close to 61. This means that the range of changes in the amount of energy on the panels is very small compared to the luminance in the space, and the changes around the average value are very close. In addition, Spearman's correlation considers the relationship between two variables very little and shows a negative (indirect) relationship, and there is no significant relationship between the two variables, in other words, it is much more than zero. From this result, it can be seen that the type of NKAF movement is very influential between these two variables.

Figure 8

Fig. 8. Top: the amount of radiation on the panels and the illuminance in the space are shown at the same time. Bottom: analysis data by Spearman correlation to depict convergence between the outdoor criteria (collecting the solar radiation as electrical sources) and indoor criteria (Illuminance).

5. Toward the post-processing simulation and extracting the adaptability logic for facade adaptability annual program

5.1. The first logic; the ray tracing-based logic

As mentioned in the methodology section, after the simulation process in the post-processing stage, the Facade Adaptability Annual Program is required for the NKAF to perform the annual analysis. For this purpose, in this research, some creative methods for preparing The Facade Adaptability Annual Program have been presented. Due to the nature of the type of facade movement and the principles of adaptability based on environmental factors, maximum efforts have been made in line with the adaptability of the NKAF with ray tracing-based logic.

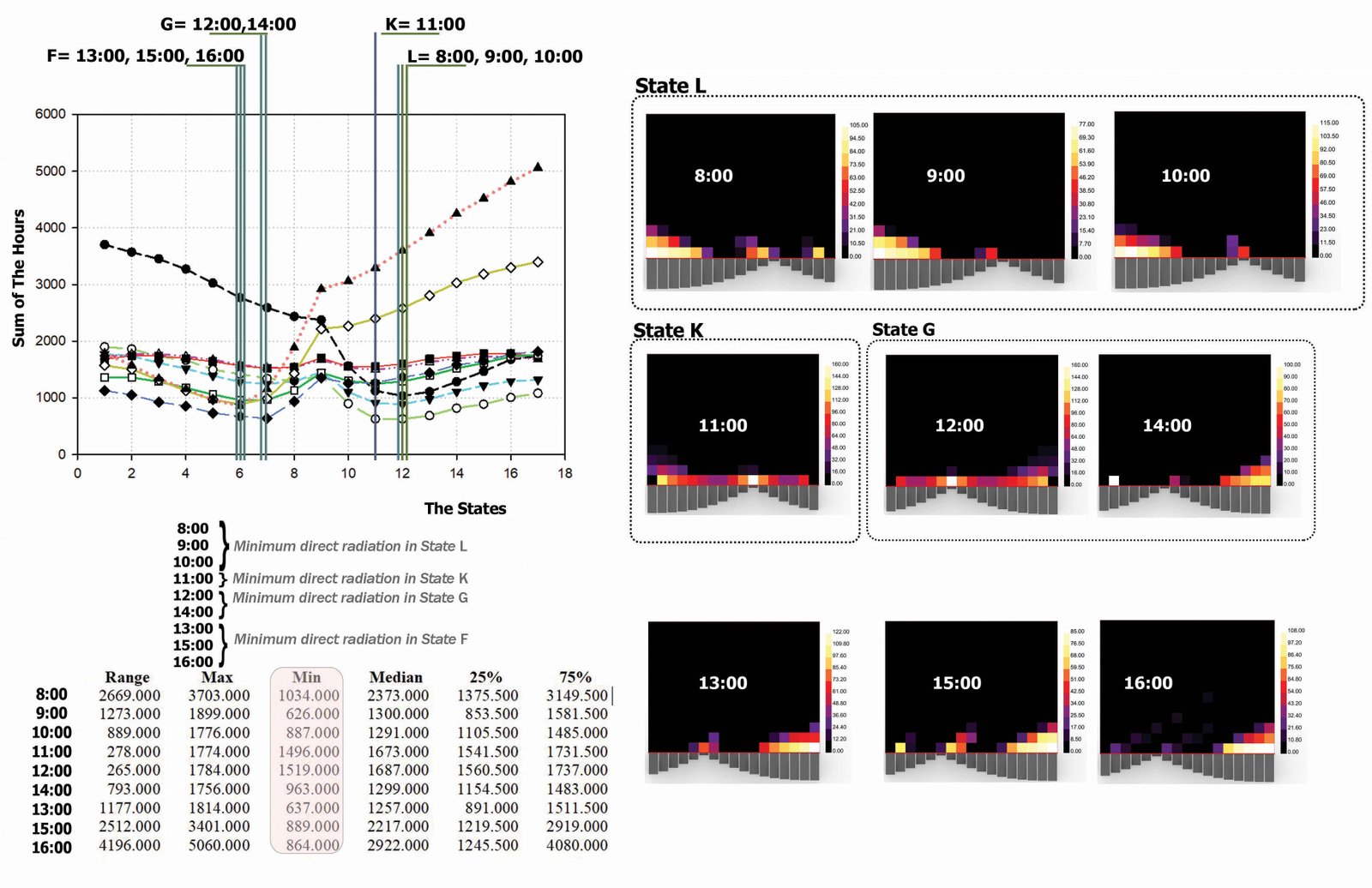

The first logic described in Fig. 9, is adjusted according to the simulation based on the amount of direct beams into the space. In this logic, every hour in the whole year (for example, steps in the format of 8 hours in 12 months of the year), all the NKAF states are simulated, in other words, 17 states are simulated in nine hourly steps and their information is shown in Fig. 3. In this logic, every state that shows the lowest radiation for the desired hour in the space is fixed. Based on the results obtained in this logic, the NKAF must not move in a typical rhythm. Because the lowest radiation in some hours is only specified in one state or sometimes, it moves backward. As a result, this logic suggests an almost unusual program.

Figure 9

Fig. 9. The first logic (Logic 1): Ray tracing-based NKAF simulation. This logic identifies the optimal NKAF state for minimizing radiation by simulating all 17 states hourly throughout the year. See Appendix A for the detailed schedule.

5.2. The second logic; the solar motion trajectory

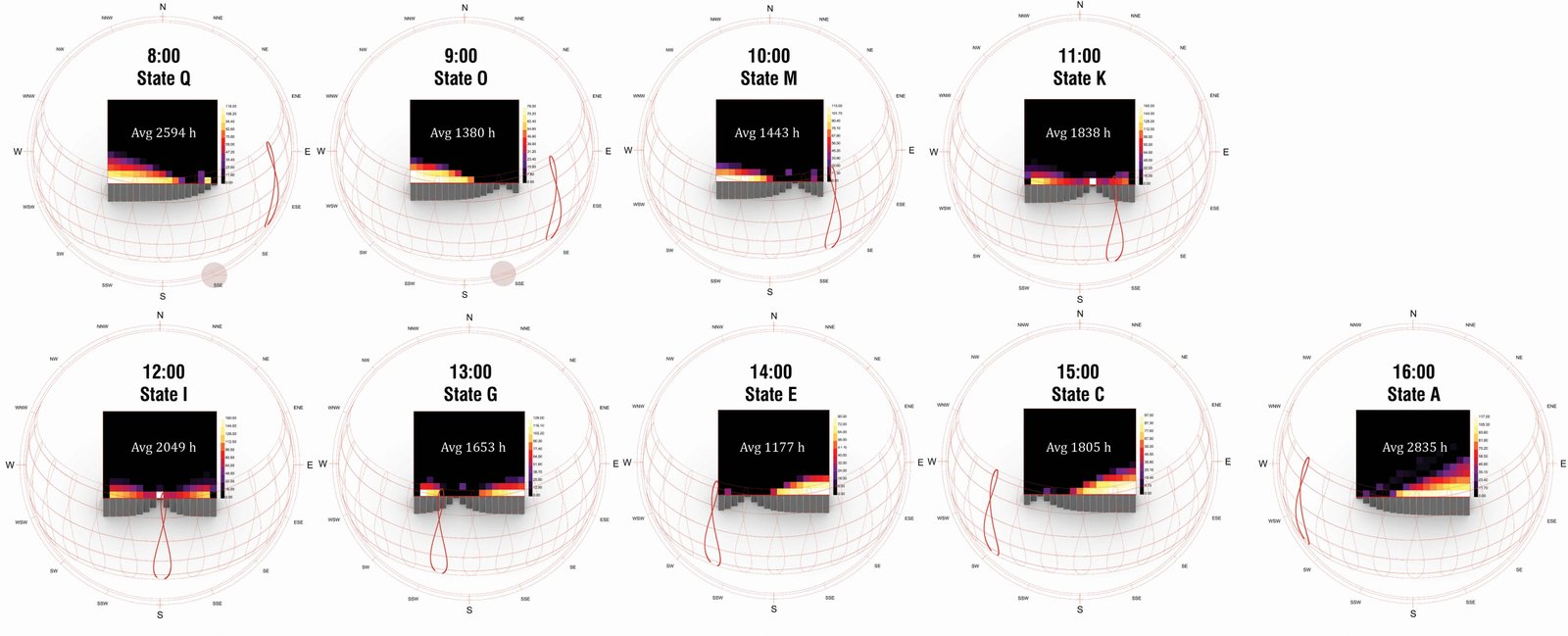

The logic of the second adaptability is shown in Fig. 10. In this logic, a mental imagination of the movement of the sun (imagined solar motion trajectory) on the facade of the building is planned so that the covering part of the NKAF follows the movement of the sun according to the angle of the sun's beams. In other words, each hour can evoke the angle of the sun's rays, and the covering part in the NKAF can be adjusted for each hour. As shown in Fig. 10, the Q state is selected for 8 o'clock and the rest of the states are O, M, K, I, G, E, C, and A for 9:00, 10:00, 11:00, 12:00, 13:00, 14:00, 15:00, and 16:00 respectively are fixed. The results of the distribution patterns of direct rays in the mentioned states for the NKAF show that the covering part for the NKAF has completely blocked the direct rays of the sun. Based on these results, it can be seen that this logic can work correctly.

Figure 10

Fig. 10. The second logic; the solar motion trajectory. Direct sunbeam distribution from 8:00 (state Q) to 16:00 (state A. The covering part of the NKAF effectively blocks direct sunlight by adjusting to the sun's trajectory. Refer to Appendix B for the detailed schedule.

5.3. The third logic: mobility reduction of NKAF

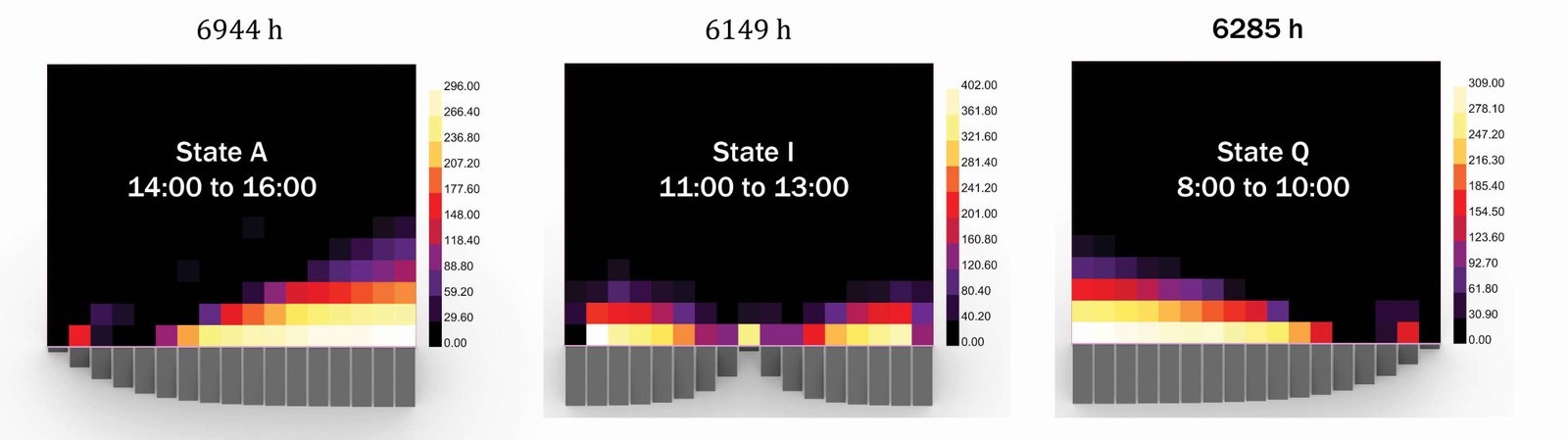

Considering the limitations in moving parts and mobility challenges, minimizing the mobility mechanism in dynamic shadings and facades is a positive strategy in order to minimize energy consumption. Accordingly, the third logic is shown in Fig. 11. This logic is set based on the mentioned challenge, which causes the movement efforts to be as low as possible while having maximum productivity. The third logic is again based on understanding the movement of the sun relative to the facade of the building in three steps. In other words, the covering part is matched in three steps. First, it is completely towards the east, then completely in the middle, and finally completely towards the west. These three changes are arranged in three-hour steps. That is, from 8:00 to 10:00 it turns to the east, 11:00 to 13:00 in the middle, and 14:00 to 16:00 the west. According to the results, the distribution patterns of direct rays also partially prove the correct operation of the states in total hours (annually).

Figure 11

Fig. 11. The third logic: mobility reduction of NKAF. The NKAF adjusts to three primary positions annually: facing east (8:00–10:00), centered (11:00–13:00), and facing west (14:00–16:00), minimizing movement while optimizing productivity. See Appendix C for the detailed schedule.

6. Results of dynamic-objects daylight simulation (post-prospecting)

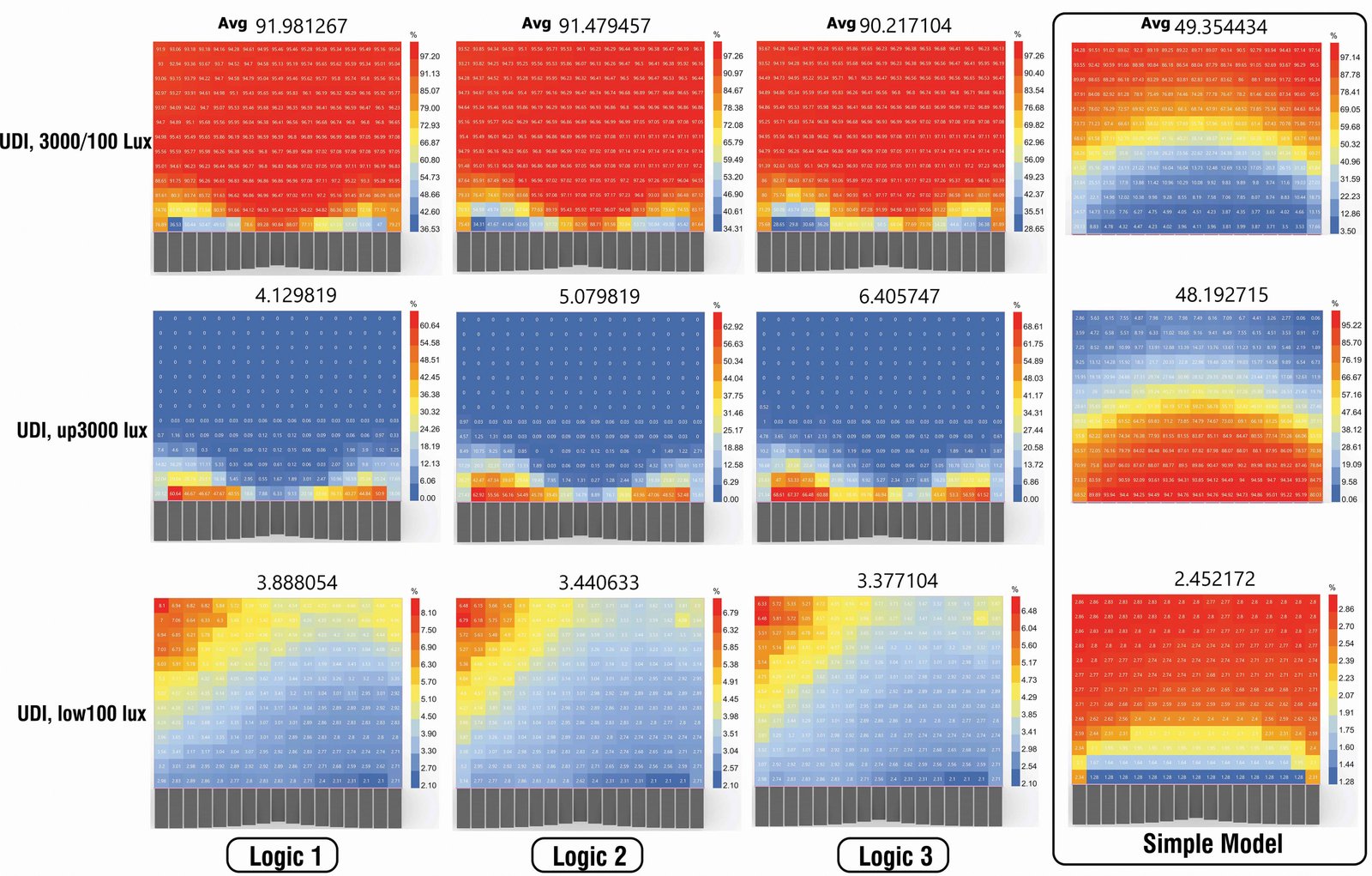

As discussed in the methodology section about the logic, one can have an imagination of the movement of the NKAF and analyze the results according to this movement imagination. Figure 12 shows the annual results of daylight in terms of UDI compared to the NKAF movement in all days of the year. As it is known, the changes in daylight efficiency (UDI) and daylight discomfort amount (UDI, low100 lux) can be clearly seen in the simple model (without the NKAF) and with the NKAF (including three extracted logics). According to the UDI metric in the range of 3000 to 100 lux, you can see the significant effect of the NKAF, so that the UDI, 100,3000 lux has reached the range of 90 from 49%. Among the logic, as we go from logic 3 to logic 1, the UDI 100,3000lux value will be improved. This means that the logic based on blocking the sunbeams (logic 1) can prove the better performance of the NKAF. According to the UDI up3000 lux, it can be concluded that the effect of the NKAF is significantly reached, in other words, radiations above 3000 lux have been significantly prevented. Based on this metric of logic 3, which has less mobility (three steps during the day) than other logic, the UDI up3000 lux has a worse situation. Naturally, following the rays of the sun is interrupted in this logic, and more rays are allowed to enter the space. UDI low100 lux does not show much difference; basically, this is because the model in question was only for testing the methodology, but in general, the values of UDI low100 lux are only available in less than 3% at the end of the room. Based on this metric, logics 1, 2, and 3, which have the NKAF, cannot be seen compared to the simple model. This means that the performance of the NKAF is perfect in preventing rays of less than 100 lux and it does not make occupants uncomfortable.

Figure 12

Fig. 12. Annual dynamic-object daylight simulation compering three logic and simple model (shading less). Adaptability Annual Program for each logic cited in Appendix A, B and C.

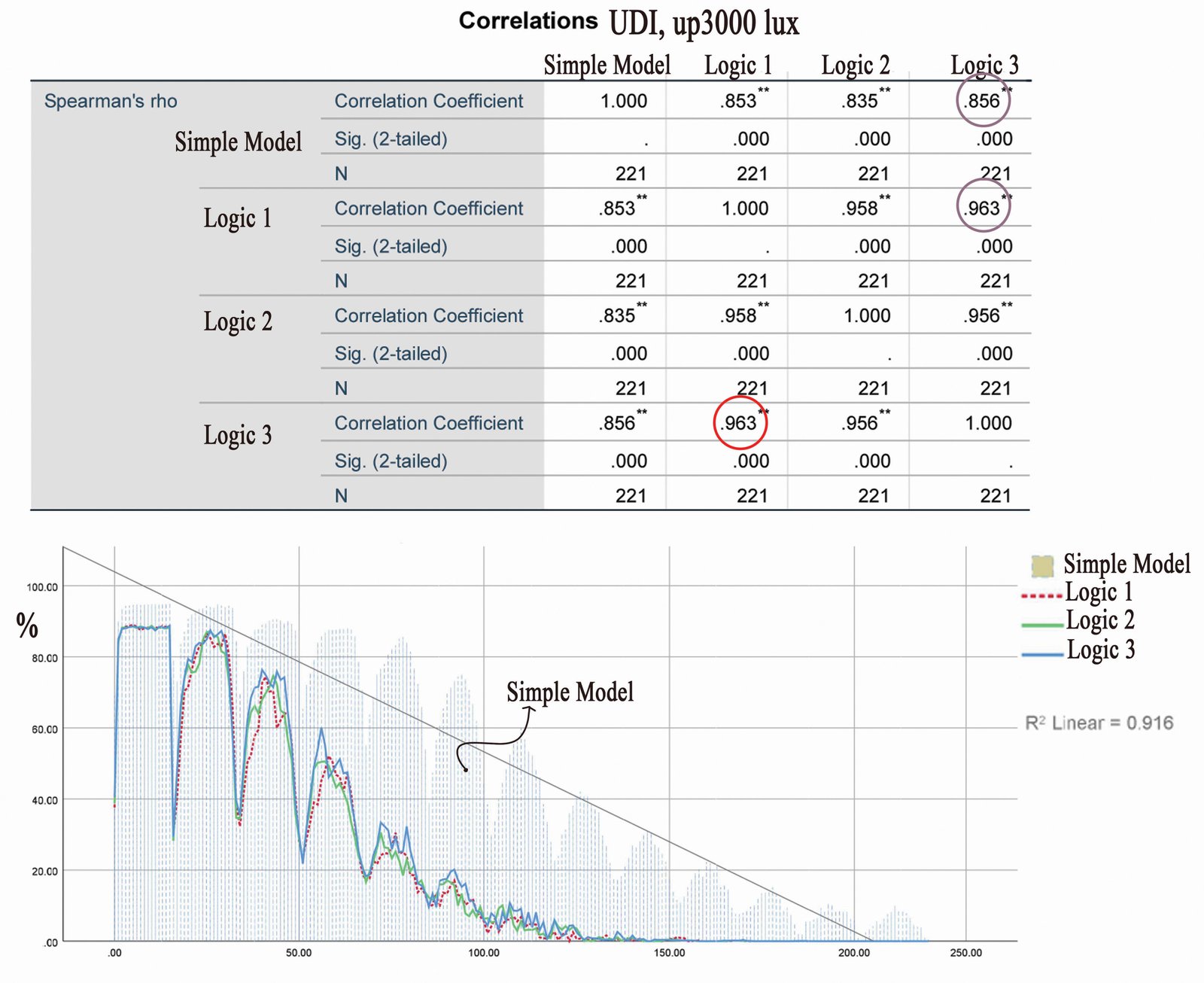

Figure 13 shows the results of the UDI up3000 lux in three logic and simple models. In the analysis of Speman's correlation, all the logic along with the simple model have been investigated by the UDI up3000 lux and their correlation. First, it should be stated that all the correlations are positive, which means that the correlation between the variables has a direct correlation. According to Spearman's results, there is a maximum correlation between the simple model and logic 3, that is, according to the minimum movement of the NKAF (only three steps during the day) in logic 3, the amount of radiation is more than 3000 lux; In other words, it can be deduced that the amount of UDI 100, 3000 lux decreases with the decrease in the NKAF activity during the day. The correlation between logic 1 and 3 is the highest among all correlations (0.963). From this, it can be concluded that logic 1 and logic 3, which are not compiled based on the default NKAF rhythm, have a direct correlation, although the average amount of UDI 100,3000 in logic 1 is the lowest.

Figure 13

Fig. 13. The results of the UDI up3000 lux in three logic and simple models. In the analysis of Speman's correlation, all the logic along with the simple model have been investigated by the UDI up3000 lux and their correlation.

It can also be seen from the diagram in Fig. 3 that logic 3 shows the values of UDA up3000 lux at the end of the space in a larger amount than the other two logics. It can be almost understood that the low mobility of the NKAF is effective in relation to the solar altitude angles, in other words, when the angle of the solar altitude angle is low and the steps of the NKAF are short, the sun's rays penetrate deeper into space. In conclusion, among the three logics—UDI 100, 3000 lux, and UDI up to 3000 lux—the third one stands out as the least effective. However, it's worth noting that the differences between them aren't very significant. Additionally, the NKAF's limited mobility to three states means it consumes less electricity, making it more economical. Consequently, among the three logics, the third one is chosen as the best option due to its energy efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

7. Multi-objective optimization to ensure the reliability of third logic (the most cost-effective)

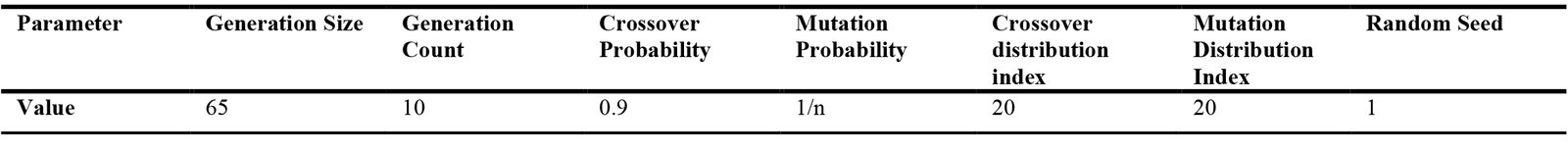

In the previous section, among three post-processing approaches, the third logic was chosen as the most suitable due to economic considerations. To ensure the reliability of the results obtained, an optimization method was employed in this section. This paper examines three objectives related to shading: movement, material, and size of each component, simultaneously aiming to improve shading functions by enhancing daylighting, sky view, and radiation on photovoltaic panels. Consequently, it must be an optimization problem that includes multiple objective functions. This study applies multi-objective optimization criteria to maximize illuminance, and irradiance on photovoltaic panels, and sky view. To obtain superior solutions that are not dominated by others in the Pareto front, a developed non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm-II (NSGA-II) is proposed. This algorithm, widely recognized for its efficiency, strives to find solutions that are both well-distributed and close to the optimal balance. It was created by Deb and his colleagues as an enhancement to the original NSGA [64]. The optimization approach in this study leverages Wallacei [65], a specialized analytical tool designed for Grasshopper.

7.1. Determining the Time Period

Analyzing all seasons and days of the year in detail is not feasible due to the time-consuming nature of multi-objective optimization and the requirement for powerful computational systems, which exceeds the capacity of this research. As a result, the analysis focuses on the most critical season, summer, with June 21 identified as the representative day. To further streamline the process and ensure cost-effectiveness, the hours of 9 a.m., 12 p.m., and 3 p.m. were selected. This selection aligns with key sun positions: east in the morning (8–10 a.m.), directly overhead at noon (11–1 p.m.), and west in the afternoon (2–4 p.m.). This approach allows for comparison of the optimization results with the third logic, enabling the determination of an appropriate movement rhythm and state for the NKAF. The findings can also be extended to other seasons as a reference.

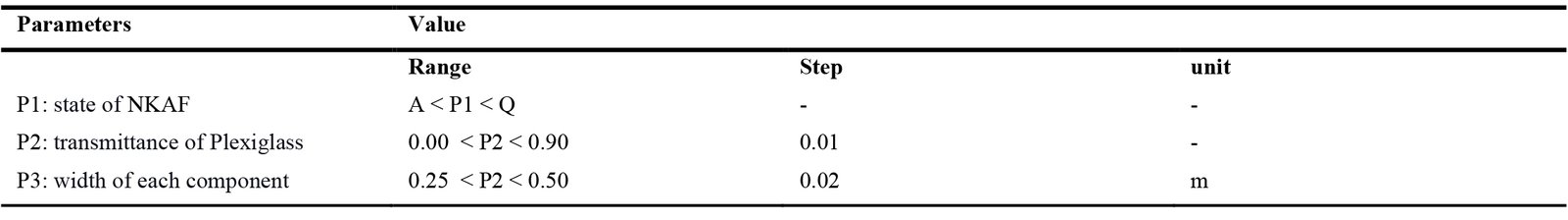

7.2. Setup and parameters

In this study, due to the computational intensity of Radiance software and its long runtime, the Generation Size and Generation Count were set to 65 and 10, respectively. Other parameters of the NSGA-II algorithm in the Wallacei plugin are detailed in Table 4. There are three objective functions in the optimization process. The first fitness objective (FO1) is the percentage of sky view from the inside. The second objective (FO2) is the average illuminance on the floor, with a threshold between 100 lux and 3000 lux. The third objective (FO3) is the average irradiation on PV panels. As shown in Table 5, the optimization approach aims to maximize all three objective functions by adjusting three parameters: the state of shading, the transmittance of Plexiglass, and the width of each shading component. These parameters are evaluated to achieve the defined goals effectively.

8. Results

In a multi-objective problem where fitness criteria conflict, optimal designs do not necessarily provide the best solution for each objective function individually. Instead, they strive for the most balanced compromise across all target functions. This study employs multi-objective optimization using Pareto's statistical method to evaluate and integrate different performance grades. Various non-dominant grades are assessed, and optimal values in the solution graph are identified.

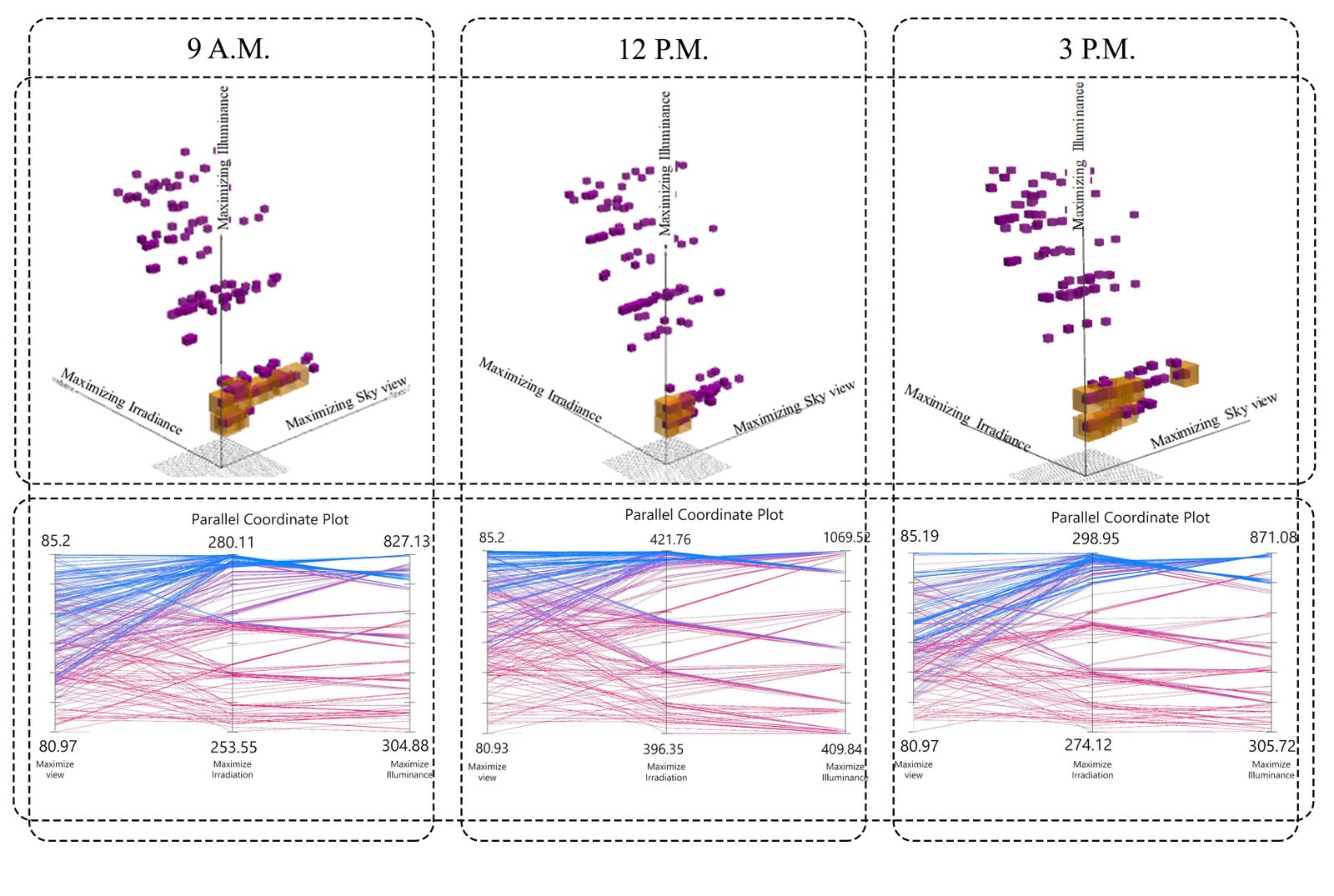

As shown in Fig. 14, for each specific time (9 a.m., 12 p.m., and 3 p.m.), a three-dimensional network is created in Wallacei Grasshopper, representing three objectives. The sky view is plotted along the X-axis, irradiance along the Y-axis, and illuminance along the Z-axis. The finest feasible solutions in the Pareto front provide valuable insights for identifying the best compromises. In the objective spaces for 9 a.m., 12 p.m., and 3 p.m., 26, 11, and 33 Pareto solutions (boxes) are recognized, respectively, for simultaneously balancing all response variables, as shown in Fig. 14. Although the Pareto front suggests 70 solutions, analyzing all of them is beyond the scope of this research. Thus, three optimum solutions from the final generations in each Pareto front are selected, analyzed, and presented in Table 6.

- The Pareto front in 14 illustrates the final generation of individuals at three times of the day:

- At 9 a.m., a high sky view of 85.2%, irradiance around 298 W/m², and illuminance around 827 lux are achievable.

- At 12 p.m., the high sky view remains consistent at 85.2%, while irradiance increases to approximately 421 W/m², and illuminance rises to 1060 lux.

- At 3 p.m., the sky view slightly decreases to 85.1%, with irradiance and illuminance measuring around 298 W/m² and 871 lux, respectively.

Figure 14

Fig. 14. The Pareto front (above) and parallel coordinate plot (below) of multiple optimizations at 9 AM, 12 PM, and 3 PM. In the 3D Pareto front, the optimal solutions are represented by yellow boxes, and in the parallel coordinate plot, the optimal solutions are represented by blue lines.

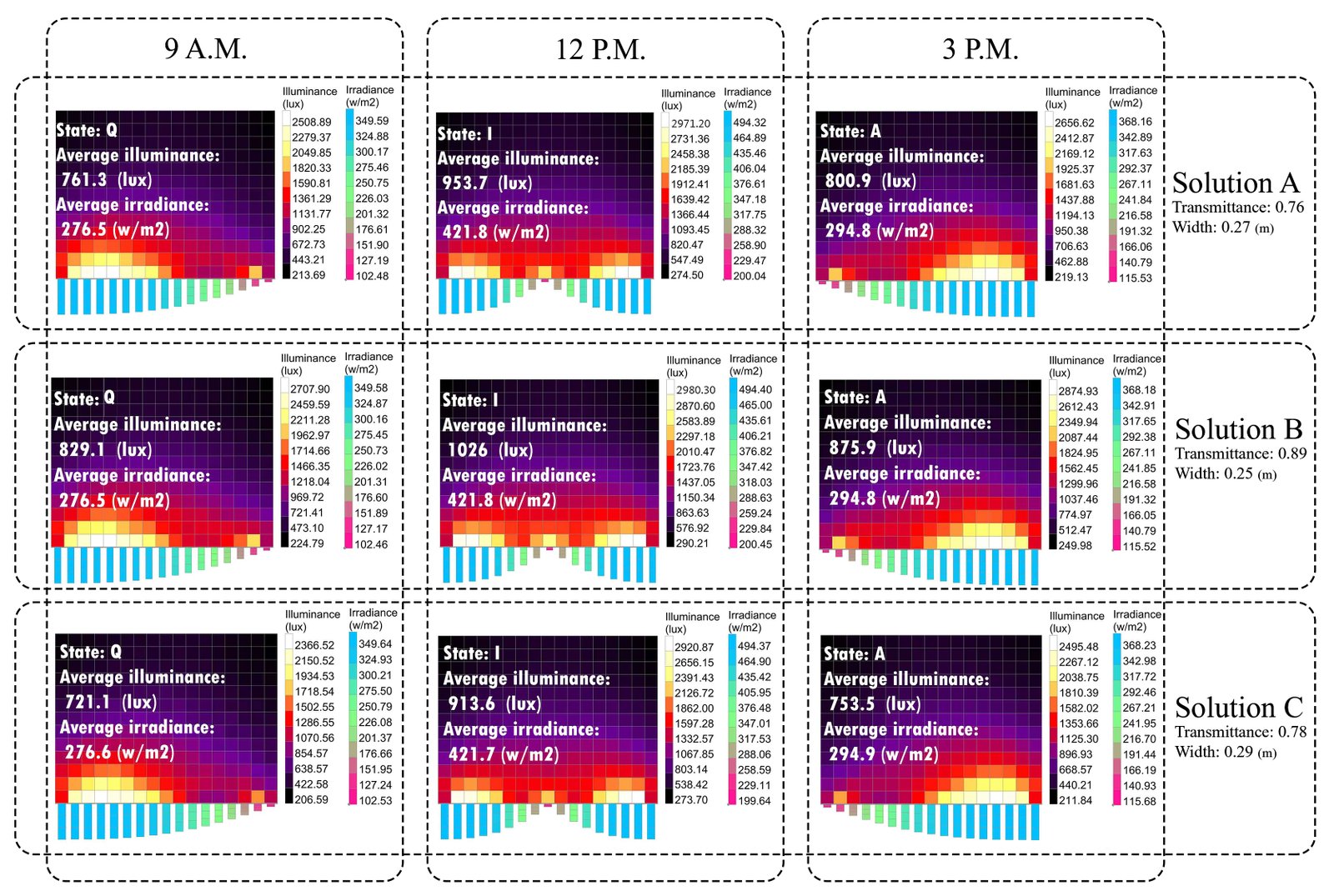

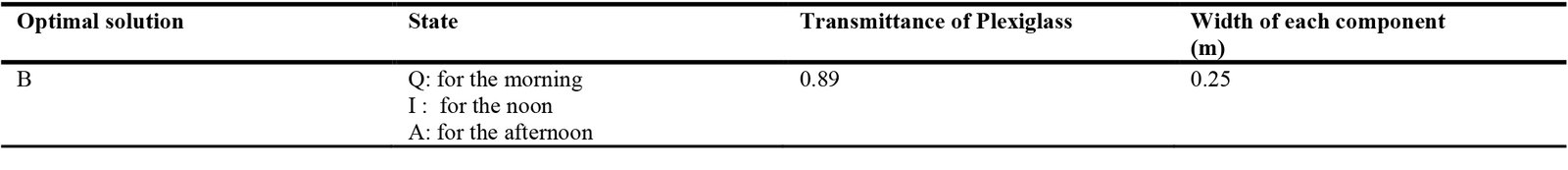

The analysis reveals that the sky view range is limited, with optimal solutions improving it by about 5%. The difference in irradiance between low and high values across all scenarios is approximately 25 W/m², while illuminance varies significantly—by over 500 lux—between the worst and best solutions, highlighting the substantial impact of variables on office room lighting. As shown in Table 6, state Q of the NKAF is the optimal solution for 9 a.m., where changes in component size have no significant effect on irradiance. By 12 p.m., both states I and Q are viable, though state I yields superior results. At 3 p.m., state A dominates, with a decrease in component width leading to an increase in illuminance.

8.1. A Decision-Making Analysis to Specify the Optimal Solution

In multi-objective optimization, identifying a single "best" solution is often infeasible due to conflicting objectives. However, for the NKAF, selecting the most suitable option among the available solutions is necessary to establish optimal conditions.

As shown in Fig. 15, at 9 a.m., the sky view and irradiance are nearly identical across all solutions, making illuminance the decisive criterion. With an illuminance of 761.3 lux—approximately 100 lux higher than solution two and 300 lux higher than solution three—solution one is deemed optimal for this time. At 12 p.m., solution one also stands out, achieving an illuminance of 1026 lux, about 100 lux greater than the other solutions, and is therefore selected. At 3 p.m., the differences in sky view and irradiance remain negligible, so the third solution, with an illuminance of 754.5 lux—approximately 100 lux higher than the alternatives—is chosen as the optimal option.

Figure 15

Fig. 15. A comparison of illuminance and irradiance among solutions (A,B,C) to achieve the optimal one.

Given the varying transmittance of Plexiglass and component widths in the selected solutions across different times, it is essential to determine a single, unified configuration for the NKAF. To achieve this, the attributes of the three selected solutions are generalized to accommodate all periods. From 9 a.m., solution A is identified with a transmittance of 0.76 and a width of 0.27 m. From 12 p.m., solution B features a transmittance of 0.89 and a width of 0.25 m. Finally, from 3 p.m., solution C includes a transmittance of 0.78 and a width of 0.29 m. As illustrated in Fig. 15, states Q, I, and A correspond to 9 a.m., 12 p.m., and 3 p.m., respectively, across all solutions. Since the differences in sky view percentage among the solutions are insignificant, further simulation for this parameter is unnecessary. However, irradiance and illuminance are compared across all periods for the three solutions. Figure 15 shows that while average irradiance does not vary significantly, solution B consistently exhibits higher average illuminance across all periods. Specifically, solution B achieves average illuminance values of 829.1 lux, 1026 lux, and 975.9 lux at 9 a.m., 12 p.m., and 3 p.m., respectively, outperforming the other solutions. Thus, solution B is identified as the most suitable overall configuration for the NKAF.

Ultimately, a comparison between the third logic of post-processing simulation and multi-objective optimization culminates in determining an optimal state and model for the NKAF. The optimal condition for the NKAF is shown in (Table 7).

9. Discussion

The primary challenge was integrating and combining two functional-distinct facade types: dynamic PV facades, which aim to maximize solar radiation for energy generation, and kinetic adaptive facades, which prioritize enhancing indoor conditions and occupant comfort. Balancing these dual objectives required careful consideration of morphology, mobility strategies, and material selection.

This study effectively combined kinetic adaptive facades with PV panels and Plexiglas material, introducing NKAF strategy that not only enhances daylight performance but also contributes to energy efficiency. The significant improvement in UDI highlights the facade's capability to balance human comfort with energy reduction.

The optimal improvements were further evaluated to ensure compliance with current building performance codes and standards. To qualify for the LEED v4.1 view quality, at least 75% of occupied floor areas must have access to visibility of the outdoor natural environment [40]. The NKAF optimal solutions ideally met this requirement, with all obtained sky view values at or above 85%, as shown in Table 6. Furthermore, the ASE metric based on LEED IEQ-Daylight LM-83 [57] is largely satisfactory, with ASE values generally below 10%. Only in the three western-facing states (A, B, and C) did ASE values slightly exceed this threshold, reaching just under 12%, as shown in Fig. 7.

The second challenge addressed in this study was the advancement of dynamic facade simulation methods. Traditional approaches often rely on parametric simulations, which may oversimplify real-world conditions. In contrast, this study introduced a cutting-edge post-processing method using Radiance software. This approach simulated both dynamic environments and facades, enhancing the accuracy and comprehensiveness of daylight performance assessments.

Comparative analysis with previous studies underscored the novelty of the post-processing method in dynamic facade simulation. Unlike conventional parametric simulations, which often lack dynamic fidelity, this study's approach offered a more nuanced understanding of NKAF performance under varying environmental conditions. For example, in [17], Akimov showed that the study did not address optimizing individual element shapes or automating their openings to enhance occupants' comfort affected by facade movements. The scheduling and type of movement in dynamic facades, coupled with automation, could potentially lead to user discomfort. Duc Minh Le and his colleagues, in their paper [40], applied a robust multi-criteria decision-making framework to determine the unique optimal design for six different climate zones. This was a dynamic-environment with fixed facade simulation, and it was suggested that a personalized real-time control strategy be applied later. Kim and colleagues [39] proposed a gearless and compliantly adaptive climate-responsive skin panel. However, their study, according to conventional simulation, lacked the dynamic environment aspect. In another research [42], a framework was applied that supports kinetic facades by Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithms; however, it did not consider dynamic environments and facades. In comparison to previous papers, by considering the movement of the object (NKAF) and the environment, this simulation approach becomes more pioneering, realistic, and precise, effectively meeting the multifunctional facade goals.

However, like other research, this paper is not without limitations. The simulations and optimization to determine the optimal solution were only carried out during the most critical season, summer, and on its most crucial day, June 21st. This can be considered a limitation of the research. In future studies, the period of time can be more specifically extended. Moreover, since Radiance is a heavy engine requiring advanced systems, the Generation Size and the Generation Count were set to 65 and 10, respectively. Although these were sufficient for this paper, these numbers can be increased for more accuracy. In the future, this novel post-processing approach can be applied to different types of kinetic facades and daylight simulations.

10. Conclusion

This study introduces the NKAF as an innovative solution for balancing human comfort with energy reduction in office buildings. The NKAF integrates dynamic shading with photovoltaic panels, providing a multifunctional and energy-efficient design. However, integrating such kinetic facades presents challenges due to their complex, multi-functional nature. This paper aimed to optimize energy efficiency while enhancing indoor comfort.

Key findings from the study are summarized as follows:

- Daylighting Improvement: The NKAF design significantly enhanced useful daylight illuminance (UDI), increasing the percentage of space within the 100-3000 lux range from 49% to 90%, indicating a substantial improvement in daylighting conditions.

- Advancement in Daylight Simulation: This research introduced an innovative post-processing method for simulating both dynamic environments and dynamic facades, a major advancement over traditional parametric simulations. This method utilized Radiance software, enabling more accurate and efficient simulations.

- Dynamic Facade Simulation: Three logic options were explored for simulating dynamic facades: ray tracing-based, solar motion trajectory, and mobility reduction. The mobility reduction logic was selected for its cost-effectiveness and superior energy efficiency in simulating dynamic facades.

- Optimization and Framework Development: The study applied multiple optimization techniques, including NSGA-II, to compare the performance of the NKAF system. The results led to the development of an optimal framework for simultaneously addressing energy efficiency and occupant comfort.

- Recommendations for Future Research: The proposed framework provides valuable insights for future studies on kinetic facades, offering a foundation for designing energy-efficient and occupant-friendly dynamic facades.

Appendix A.

A.1. The first logic; the ray tracing-based logic

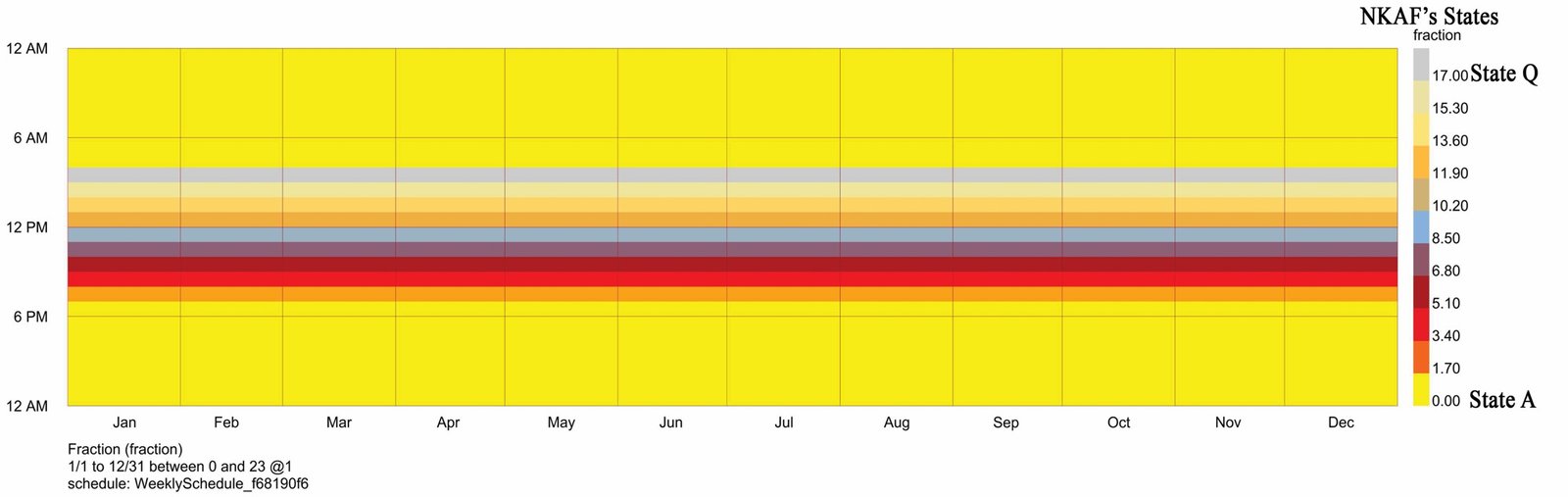

As demonstrated in Fig. 16, an annual schedule is obtained to input the data to move NKAF in the daily profile for the annual dynamic-objects daylight simulation. This profile is achieved in terms of direct sunbeams (the maximum of NKAF’s shading).

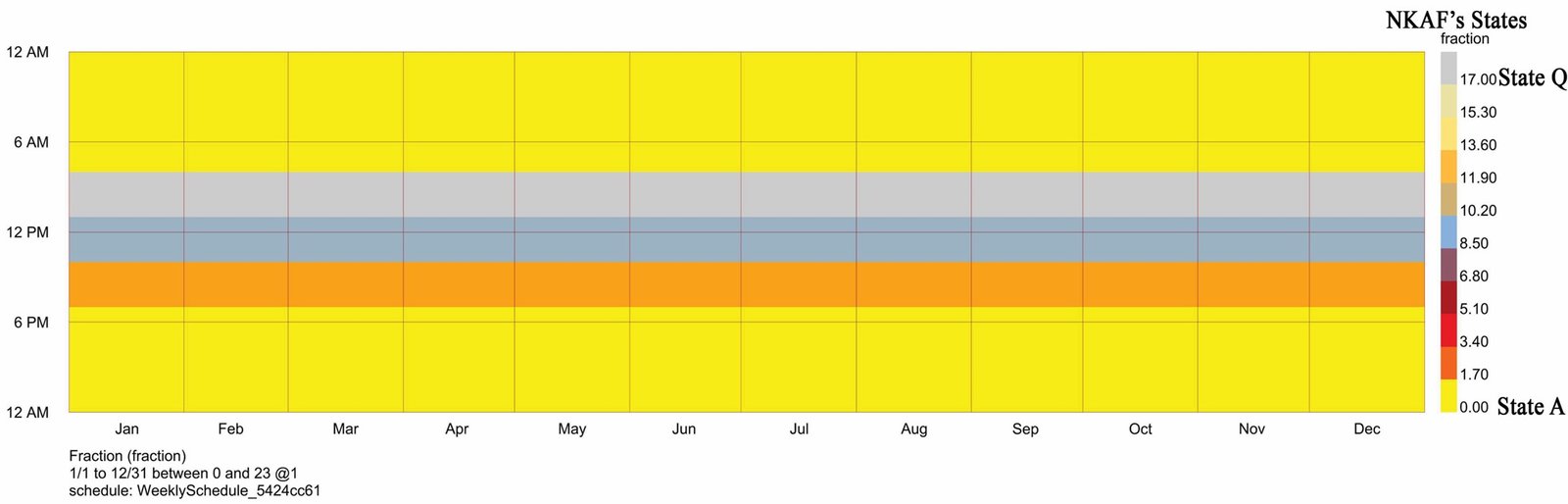

A.2. The second logic; based on the solar motion trajectory

As demonstrated in Fig. 17, this profile is arranged based on the imagination of the sun's trajectory.

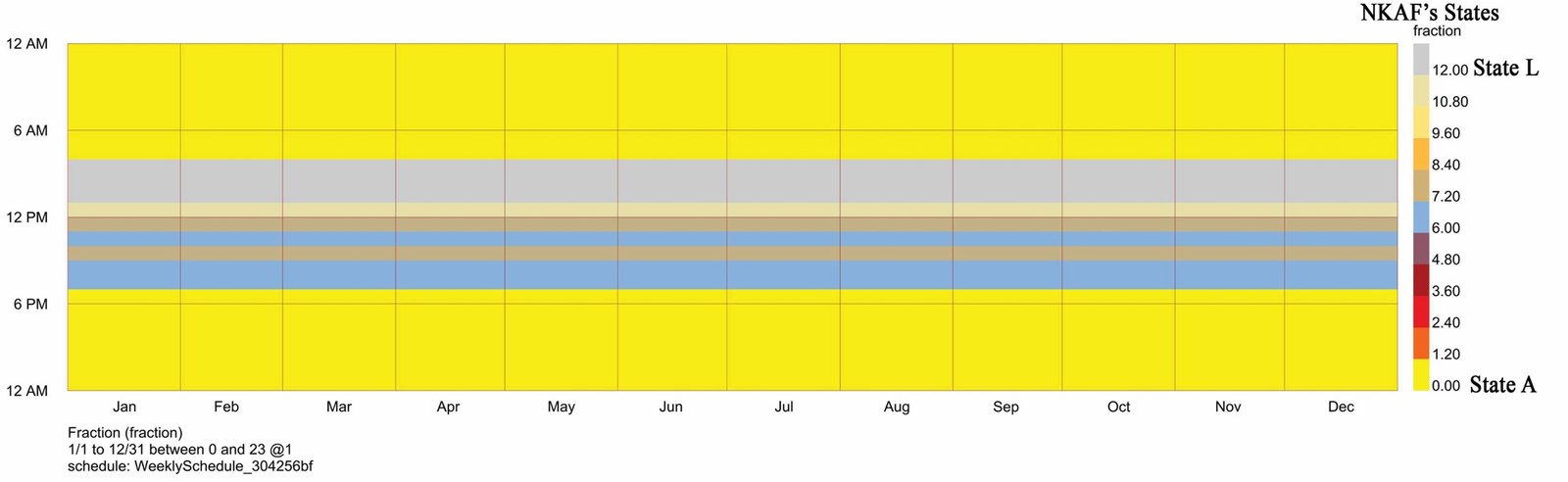

A.3. The third logic: mobility reduction of NKAF

As demonstrated in Fig. 18, this profile is arranged based on reducing the mobility of the NAKF; since the number of sequence of NKAF’s movement causes increasing the electrical load, this strategy will overcome that problem.

Acknowledgement

Contributions

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- S. Attia, Net Zero Energy Buildings (NZEB): Concepts, frameworks and roadmap for project analysis and implementation, 1st ed., Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2018, pp. 1-350.

- Y. Al Horr, M. Arif, A. Kaushik, A. Mazroei, M. Katafygiotou, E. Elsarrag, Occupant productivity and office indoor environment quality: A review of the literature, Building and Environment, 105 (2016) 369-389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.06.001

- A. Goharian, Designerly optimization of devices (as reflectors) to improve daylight and scrutiny of the light-well's configuration, in: Proceedings of the Building Simulation Conference, Glasgow, UK, 1-3 September 2022, pp. 1-24.

- L. Edwards, P. Torcellini, Literature review of the effects of natural light on building occupants, in: Proceedings of the Conference on Natural Light in Architecture, Chicago, USA, 15-17 May 2002, pp. 100-115. https://doi.org/10.2172/15000841

- H. N. Rafsanjani, C.R Ahn, M. Alahmad, A review of approaches for sensing, understanding, and improving occupancy-related energy-use behaviors in commercial buildings, Energies, 8 (2015) 10996-11029. https://doi.org/10.3390/en81010996

- M. Heirani Pour, R. Fayaz, M. Mahdavinia, Optimization of Window Dimensions Regarding Light and Heat Parameters in Residential Buildings of Cold Climate; Case Study: Ilam City, Armanshahr Architecture & Urban Development, 14 (2021) 91-101.

- M. Ganjimorad, J.D. Fernandez, and Milad Heiranipour, Impact of wind in urban planning: A comparative study of cooling and natural ventilation systems in traditional Iranian architecture across three climatic zones, Architecture Papers of the Faculty of Architecture and Design STU, 29 (2024), 15-29. https://doi.org/10.2478/alfa-2024-0020

- A. Tabadkani, A. Roetzel, H. X. Li, A. Tsangrassoulis, Design approaches and typologies of adaptive facades: A review, Automation in Construction, 121 (2021) 103450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103450

- U. Knaack, A. Luible, M. Overend, L. Aelenei, M. Perino, F. Wellershof, M. Brzezicki, Adaptive Facade Network Europe, 1st ed., TU Delft Open: Delft, Netherlands, 2015, pp. 1-250.

- D. Aelenei, L. Aelenei, C. P.Vieira, Adaptive Façade: concept, applications, research questions, Energy Procedia, 91 (2016) 269-275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2016.06.218

- S. M. Hosseini, M. Mohammadi, A. Rosemann, T. Schröder, J. Lichtenberg, A morphological approach for kinetic façade design process to improve visual and thermal comfort, Building and Environment, 153 (2019) 186-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.02.040

- S. M. Hosseini, S. Heidari, S. Attia, J. Wang, G. Triantafyllidis, Biomimetic kinetic façade as a real-time daylight control: complex form versus simple form with proper kinetic behavior, Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-03-2024-0090

- M. Shahinpoor, Biomimetic robotic Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula Ellis) made with ionic polymer metal composites, Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, 6, no. 4 (2011) 046004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-3182/6/4/046004

- R.C.G.M. Loonen, M. Trčka, D. Cóstola, J.L.M. Hensen, Climate adaptive building shells: State-of-the-art and future challenges, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 25 (2013) 483-493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.04.016

- S. Samadi, E. Noorzai, L.O. Beltrán, S. Abbasi, A computational approach for achieving optimum daylight inside buildings through automated kinetic shading systems, Frontiers of Architectural Research, 9 (2020) 335-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2019.10.004

- S. Zhao, A.L Chen, Y.S. Wang, C. Zhang, Continuously tunable acoustic metasurface for transmitted wavefront modulation, Physical Review Applied, 10 (2018) 054066. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.10.054066

- L. Akimov, A. Bezborodov, V. Badenko, Example-based dynamic façade design using the facade daylighting performance improvement (FDPI) indicator, Build. Simul, 16, (2023) 2261-2283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12273-023-1073-6

- A. Tabadkani, A. Nikkhah Dehnavi, F. Mostafavi, H. Ghorbani Naeini, Targeting modular adaptive façade personalization in a shared office space using fuzzy logic and genetic optimization, Journal of Building Engineering, 69 (2023) 106118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106118

- D.K. Bui, T.N. Nguyen, A. Ghazlan, N.T Ngo, Tuan Duc Ngo, Enhancing building energy efficiency by adaptive façade: A computational optimization approach, Applied Energy, 265 (2020) 114797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.114797

- S. Attia, S. Bilir, T. Safy, C. Struck, R. Loonen, F. Goia, Current trends and future challenges in the performance assessment of adaptive façade systems, Energy and Buildings, 179 (2018) 165-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.09.017

- S. M. Hosseini, H. Heiranipour, J. Wang, L.E Hinkle, G. Triantafyllidis, S. Attia, Enhancing Visual Comfort and Energy Efficiency in Office Lighting Using Parametric-Generative Design Approach for Interactive Kinetic Louvers, Journal of Daylighting, 11 (2024) 69-96. https://doi.org/10.15627/jd.2024.5

- C. M. Lampert, Smart switchable glazing for solar energy and daylight control, Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 52 (1998) 207-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-0248(97)00279-1

- S. M. Al-Masrani, K. M. Al-Obaidi, Dynamic shading systems: A review of design parameters, platforms and evaluation strategies, Automation in Construction, 102 (2019) 195-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.01.014

- M. Arnesano, B. Bueno, A. Pracucci, S. Magnagni, O. Casadei, G. M. Revel, Sensors and control solutions for Smart-IoT façade modules, in: 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Measurements & Networking (M&N), pp. 1-6. IEEE, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/IWMN.2019.8805024

- Barozzi, Marta, J. Lienhard, A. Zanelli, C. Monticelli, The sustainability of adaptive envelopes: developments of kinetic architecture, Procedia Engineering, 155, (2016), 275-284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.029

- P. Jayathissa, Z. Nagy, N. Offedu, A. Schlueter, Numerical simulation of energy performance, and construction of the adaptive solar façade, in: Advanced Building Skins, International Conference on Building Envelope Design and Technology, Technical University of Graz, Austria, 23-24 April 2015, pp. 47-56.

- D. Roche, H. Outhred, R.J Kaye, Analysis and control of mismatch power loss in photovoltaic arrays, Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications, 3 (1995) 115-127. https://doi.org/10.1002/pip.4670030204

- N. N. Castellano, Optimal displacement of photovoltaic array's rows using a novel shading model, Applied Energy, 144 (2015) 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.060

- Kuipers, N., From Static to Kinetic: The Potential of Kinetic Façades in Care Hotels, in: aE-Intecture-studio 14, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, 5 June 2015, pp. 1-69.

- B. Svetozarevic, M. Begle, P. Jayathissa, S. Caranovic, R. F. Shepherd, Z. Nagy, I. Hischier, J.Hofer, A. Schlueter, Dynamic photovoltaic building envelopes for adaptive energy and comfort management, Nature Energy, 4 (2019) 671-682. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0424-0

- M.V Nielsen, S. Svendsen, L.B Jensen, Quantifying the potential of automated dynamic solar shading in office buildings through integrated simulations of energy and daylight, Solar Energy, 85, no. 5 (2011), 757-768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2011.01.010

- S. M. Hosseini, M. Mohammadi, T. Schröder, O. Guerra-Santin, Integrating interactive kinetic façade design with colored glass to improve daylight performance based on occupants' position, Journal of Building Engineering, 31 (2020), 101404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101404

- S. M. Hosseini, M. Mohammadi, F. Fadli, Biomimetic kinetic shading facade inspired by tree morphology for improving occupant's daylight performance, Journal of Daylighting 8 (2021) 65-85. https://doi.org/10.15627/jd.2021.5

- S. M. Hosseini, M. Mohammadi, T. Schröder, O. Guerra-Santin, Bio-inspired interactive kinetic façade: Using dynamic transitory-sensitive area to improve multiple occupants' visual comfort, Frontiers of Architectural Research, 10 (2021) 821-837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2021.07.004

- A. K. Athienitis, G. Barone, A. Buonomano, A. Palombo, Assessing active and passive effects of façade building integrated photovoltaics/thermal systems: Dynamic modelling and simulation, Applied Energy, 209, (2018), 355-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.09.039

- H. Ghorbani Naeini, A. Norouziasas, F. Piraei, M. Kazemi, M. Kazemi, M. Hamdy, Impact of building envelope parameters on occupants’ thermal comfort and energy use in courtyard houses, Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 20 (2024) 1725-1751. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2023.2254294

- A. Tabadkani, A. Roetzel, H. X. Li, A. Tsangrassoulis, A review of automatic control strategies based on simulations for adaptive facades, Building and Environment, 175, (2020), 106801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106801

- M. Valitabar, M., A. GhaffarianHoseini, A. GhaffarianHoseini, A., & Attia, S, Advanced control strategy to maximize view and control discomforting glare: a complex adaptive façade, Architectural engineering and design management, 18, no. 6, (2022), 829-849. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2022.2032576

- M.J. Kim, B.G. Kim, J.S. Koh, H. Yi, Flexural biomimetic responsive building façade using a hybrid soft robot actuator and fabric membrane, Automation in Construction, 145, (2023), 104660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104660

- D.M. Le, D.Y. Park, J. Baek, P. Karunyasopon, S. Chang, Multi-criteria decision making for adaptive façade optimal design in varied climates: Energy, daylight, occupants' comfort, and outdoor view analysis, Building and Environment, 223, (2022), 109479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109479

- S. M. Hosseini, S. Heidari, General morphological analysis of Orosi windows and morpho butterfly wing's principles for improving occupant's daylight performance through interactive kinetic façade, Journal of Building Engineering, 59 (2022), 105027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105027

- S. O. Sadegh, E. Gasparri, A. Brambilla, A. Globa, Kinetic facades: An evolutionary-based performance evaluation framework, Journal of Building Engineering, 53 (2022), 104408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104408

- A. Goharian, M. Mahdavinejad, A novel approach to multi-apertures and multi-aspects ratio light pipe, Journal of Daylighting, 7 (2020), 186-200. https://doi.org/10.15627/jd.2020.17

- F. Rezaei, H. Sangin, M. Heiranipour, S. Attia, Multi-objective Optimization of Window and Light Shelf Design in Office Buildings to Improve Occupants' Thermal and Visual Comfort, Journal of Daylighting, 11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.15627/jd.2024.4

- Y. Ibrahim, T. Kershaw, P. Shepherd, A Methodology for Modelling Microclimate: A Ladybug-Tools and ENVI-Met Verification Study, in: Proceedings of the 35th PLEA Conference Sustainable Architecture and Urban Design: Planning Post Carbon Cities, 2020.

- T. Raziei, Climate of Iran according to Köppen-Geiger, Feddema, and UNEP climate classifications, Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 148 (2022), 1395-1416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-022-03992-y

- W. Wang, S. Li, S. Guo, M. Ma, S. Feng, L. Bao, Benchmarking Urban Local Weather with Long-term Monitoring Compared with Weather Datasets from Climate Station and EnergyPlus Weather (EPW) Data, Energy Reports, 7 (2021), 6501-6514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.09.108

- C. F. Reinhart, Effects of Interior Design on the Daylight Availability in Open Plan Offices, in: Proceedings of the 2002 American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE) Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings, 3 (2002), 309-322.

- C. R. S. Reinoso, D. H. Milone, R. H. Buitrago, Simulation of photovoltaic centrals with dynamic shading, Applied Energy, 103 (2013), 278-289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.09.040

- C. Reinhart, M. Andersen, Development and validation of a Radiance model for a translucent panel, Energy and Buildings, 38 (2006), 890-904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2006.03.006

- A.G. Mainini, A. Zani, G. D. Michele, A. Speroni, T. Poli, M. Zinzi, A. Gasparella, Daylighting performance of three-dimensional textiles, Energy and Buildings, 190 (2019), 202-215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.02.036

- A. Goharian, K. Daneshjoo, M. Mahdavinejad, M. Yeganeh, Voronoi geometry for building facade to manage direct sunbeams, Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Civil Engineering, 31 (2022), 109-124. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.sace.31.2.30800

- R. Compagnon, RADIANCE: A Simulation Tool for Daylighting Systems, The Martin Centre for Architectural and Urban Studies, University of Cambridge, Department of Architecture, 1997.

- M. Sudan, R. G. Mistrick, G.N. Tiwari, Climate-Based Daylight Modeling (CBDM) for an Atrium: An Experimentally Validated Novel Daylight Performance, Solar Energy, 158 (2017), 559-571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2017.09.067

- L. Bellia, A. Pedace, F. Fragliasso, The impact of the software's choice on dynamic daylight simulations' results: A comparison between Daysim and 3ds Max Design®, Solar Energy, 122 (2015), 249-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2015.08.027

- A. Ahmad, A. Kumar, O. Prakash, A. Aman, Daylight availability assessment and the application of energy simulation software-A literature review, Materials Science for Energy Technologies, 3 (2020), 679-689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mset.2020.07.002

- L. Heschong, V:D. Wymelenberg, Van Den, V.C. Keven, M. Andersen, N. Digert, L. Fernandes, A. Keller, J. Loveland, H. McKay, R. Mistrick, B. Mosher, C. Reinhart, Z. Rogers, M. Tanteri, Approved method: IES spatial Daylight autonomy (sDA) and annual sunlight exposure (ASE), IES - Illuminating Engineering Society, (2012), pp 1-13.

- C. Reinhart, Opinion: Climate-based daylighting metrics in LEEDv4-A fragile progress, Lighting Research & Technology, 47 (2015) 388-388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477153515587613

- A. Nezamdoost, A., K. V. D. Wymelenberg, A daylighting field study using human feedback and simulations to test and improve recently adopted annual daylight performance metrics, Journal of Building Performance Simulation, 10 (2017), 471-483. https://doi.org/10.1080/19401493.2017.1334090

- A. Nabil, J. Mardaljevic, Useful daylight illuminance: a new paradigm for assessing daylight in buildings, Lighting Research & Technology, 37 (2005), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1191/1365782805li128oa

- A. Nabil, J. Mardaljevic, Useful daylight illuminances: A replacement for daylight factors, Energy and Buildings, 38 (2006), 905-913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2006.03.013

- J. Mardaljevic, M. Andersen, N. Roy, J. Christoffersen, Daylighting metrics: is there a relation between useful daylight illuminance and daylight glare probability?, in: Proceedings of the Building Simulation and Optimization Conference, BSO12, 2012.